Here is a selection of writers who have taken their cue from the artist himself, Alberto Giacometti, in an intense looking at the world. In this case, the world is the one contained within the artist’s studio. From Jean Paul Sartre and Jacques Dupin, to David Sylvester and James Lord, these writers experienced first hand the work of the artist. Unique points of view, in fact, art historical primary sources. None of these selections are mere descriptions or illustrations, rather they are true ruminations and examples of literature which have been inspired directly by visual works of art and the artist who created them.

“Portrait of Jean Paul Sartre”

1949

Pencil on paper

28.5cm x 11.2cm

Fondation Giacometti, Paris, France

In his essay on “The Quest for the Absolute” Jean Paul Sartre famously observed that this work was real evidence of the existential predicament. It was included in the catalogue for Giacometti’s 1948 exhibition at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York: Giacometti’s first major exhibition after WWII, and his first at Pierre Matisse in fourteen years. Sartre wrote:

“So we must start again from scratch. After three thousand years the task of Giacometti and contemporary sculptors is not to add new works to the galleries but to prove that sculpture is possible. . . . It is necessary to push to the limits and see what can be done. If the undertaking should end in failure, it would be impossible, in the best cases, to decide whether this meant that the sculptor had failed or sculpture itself; others would come along, and they would have to begin anew. Giacometti himself is forever beginning anew. But this is not an infinite progression; there is a fixed boundary to be reached, a unique problem to be solved: how to make a man out of stone without petrifying him. It is an all-or-nothing quest: if the problem is solved, it matters little how many statues are made.”1

“Alberto Giacometti’s Portrait of Eli Lotar III”

1965

Gelatin silver print

14 3/4” x 19”

Gitterman Gallery, New York, New York.

Not just the writers, but many photographers took an interest in this work, continuing to pay attention to the changing vision and work of this artist. Both Henri Cartier-Bresson and Herbert Matter caught iconic images of Giacometti working in his studio and walking through the streets of Paris, and it was in this particular neighborhood that Jacques Dupin would visit Alberto Giacometti. His visits were recorded in the book “Giacometti: Three Essays” and the first of these essays, “Texts for an Approach” was actually translated by the New York School poet John Ashberry. Dupin wrote on both the artist’s earlier work and how it formed the ideas for the later work.

“His not stopping means that he never stops looking at and depicting what he sees, in any circumstances and at each minute of his life, even if he is not ‘working.’ In the café he draws on his newspaper, and if he has no newspaper, his finger still runs over the marble top of the table. . . . His not stopping means too that Giacometti can only present us the rough draft of an unaccomplished, unfinished undertaking. A reflection, an approximation of reality—of that absolute reality which haunts him—and which he pursues in a kind of amorous or homicidal fury. . . .”

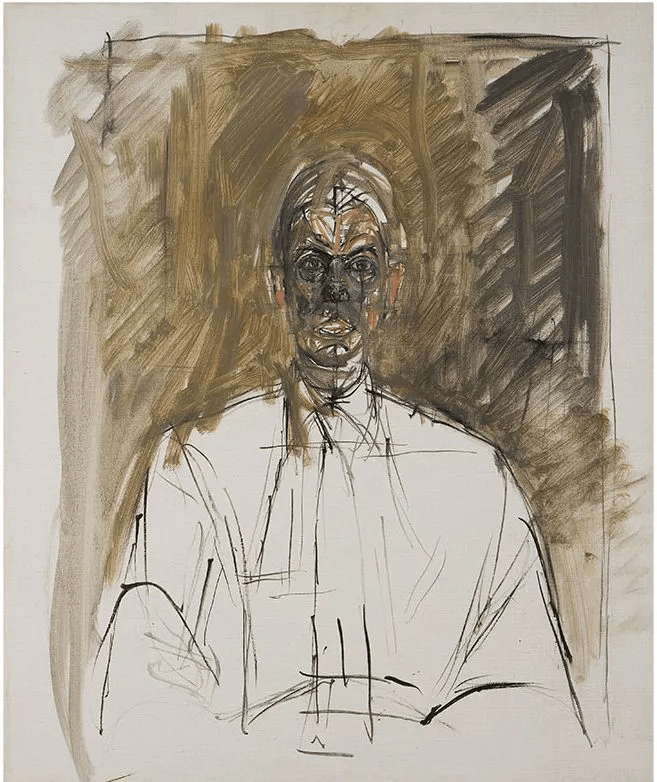

“Jacques Dupin” (No Inscription)

1965

Oil on canvas

25.75″ x 21.25″

Fondation Giacometti, Paris, France.

“. . . His optimism is thus as disproportionate with regard to the relative as his pessimism is categorical with the absolute. Yet people readily accuse him of repeating himself, of marking time. . . . In returning untiringly to the bust of Diego, the standing woman, the walking man, the portrait of the same model, he may discourage the inattentive spectator, but his austere research allows him to concentrate his ways of approaching. The slower his walk toward his goal appears, the more rapid it actually is. Each acquisition is definitive, each progress irreversible. But progress plays only with imponderable elements. A single line can stop it a whole night and hold up the whole work with the question of the exactness of its inflection. Giacometti’s not stopping means also that he does not stop advancing.”2

In addition to Jacques Dupin, the writer David Sylvester made frequent visits to Giacometti’s studio. He began these visits in the late 1940’s and continued for over forty years, including a prolonged time, sitting for his own portrait. Sylvester’s writings feature several other important artists of the time, including Henry Moore, Francis Bacon, and René Magritte, as well as this important one on Alberto Giacometti. Two examples follow:

“The sight of towering granite, stark, greyly luminous, somehow weightless, soaring to jagged splintered summits, appears in images of fragile heads and figures which are also giving form to a vision of urban reality suddenly filled with ‘an unbelievable sort of silence’ where any head was ‘as if it were something simultaneously alive and dead’, every object ‘had its own place, its own weight, its own silence, even’, was separated from other objects by ‘immeasurable chasms of emptiness’. And we, confronting the embodiments of those coalesced sensations, feel a shock of recognition of ourselves and to our mutual separateness.”3

“Portrait of David Sylvester”

1960

Oil on canvas

45 11/16″ x 35 1/16”

Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York.

“Giacometti normally has several sculptures and paintings simultaneously in progress. The thickness of the paint on most of the canvases suggests that they have been worked at over a long period. . . . Those from memory are worked on in a way that is highly characteristic of Giacometti in that it reflects a curious combination of nagging self-criticism and a desire for spontaneity. While it is in progress, and this can be over a period of a couple of years,…..it is as if the process of creation consisted of a series of rehearsals and the final rehearsal was the performance, though the performer didn’t know till afterwards that this rehearsal was to be the performance.”4

Finally, the American writer James Lord, agreed to sit for his own portrait. During this time and unbeknownst to the artist, Lord made meticulous notes and took a photograph of the portrait he had been sitting for after each of its eighteen sittings. Here are two excerpts: one from the end of the first week of sittings, and the second from the very last day. It is as if each new sitting is a new attack, seeing everything again, and a new beginning.

“Giacometti looked forward to working on Sunday because the chances of being disturbed then by visitors were less than during the week. As soon as I arrived at the studio, he told me that he hadn’t gone to bed till five and had slept very badly. But he denied feeling at all tired, and we began work at once. ‘It’s going to go well today,’ he said. ‘There’s an opening. I’ve got to make a success of the head.’ I didn’t answer, and after a few minutes he added, ‘This morning when Diego came into my room I was overcome by the construction of his head. It was as though I’d never seen a head before.’”5

“Bust of Diego, Second Version”

1962-1964

Bronze

17.44″ x 10.78″ x 6.29”

Fondation Giacometti, Paris

James Lord visited Giacometti’s studio one last time to say goodbye. They had worked on his portrait for eighteen days, sometimes making progress, sometimes not. It is a beautifully written book, sensitive to both the artist and his working process. A Giacometti Portrait has now become a classic. Always inspiring to so many artists and students and so important in understanding the thinking and painting processes employed by Alberto Giacometti.

“We went to the café. In the street he said. ‘There has been, after all, a slight progress. There’s a very small opening. In two or three weeks I’ll have an idea if there’s any hope, any chance of going on. Two or three weeks, maybe less. I have a portrait of Caroline to do, then there’s the one of Annette. And I want to do some drawings, too. I never have time for drawings anymore. Drawing is the basis for everything, though. I’d like to do some still life. But we did make a little progress, didn’t we?’”6

“Portrait of James Lord”

1964

Oil on canvas

45 5/8” x 31 3/4”

Collection of James Lord.

1 Sartre, Jean Paul; We Have only this Life to Live: Selected Essays 1939-1975; The New York Review of Books; New York, New York; 2013; p. 189.

2 Dupin, Jacques; Giacometti: Three Essays (translated by John Ashberry and Brian Evenson); Black Square Editions, Hammer Books; New York, New York; 2003; pp. 52-53.

3 Sylvester, David; Looking at Giacometti; Henry Holt and Company; New York, New York;1994; p. 113.

4 Sylvester, David; Looking at Giacometti; Henry Holt and Company; New York, New York;1994; p. 7.

5 Lord, James; A Giacometti Portrait; The Museum of Modern Art, New York, and Doubleday & Company; Garden City, New York; 1965; p. 28.

6 Lord, James; A Giacometti Portrait; The Museum of Modern Art, New York, and Doubleday & Company; Garden City, New York; 1965; p. 64.

Enjoyed this so much, thank you!

LikeLike

Thank you so much Maryann. I have always remembered our conversations regarding Giacometti and Jacques Dupin, both in my studio here in Indianapolis, and later along with Rosalie Vermette when we were all in Paris all together. So nice.

LikeLike