Since ancient times, certain stories have been handed down from one generation to another through the spoken word. They were collected by such writers as Ovid, Homer, Aesop; other later fabulist writers; and even Rumi. It was later that they were finally published. There are also times when pieces of writing, or works of art are not merely illustrations of each other, but are truly complementary, that they support one another. “The Fables of La Fontaine” are a great example of this.

“La Fontaine with the Manuscript of the Fox and the Grapes”

1785

Marble

5′ 8″ x 3′ 7 1/4″ x 4′ 2 3/4″

The Louvre, Paris, France

“The Fables of La Fontaine” were published from 1668 to 1694. Over these years several editions were illustrated by François Chauveau, Jean-Baptiste Oudry, and Gustave Doré: these becoming major works of art in their own right. They were translated into English by Walter Thornbury in 1868 and much later by the Imagist poet Marianne Moore in her “Late Poems from 1965 to 1972.”

As this ancient tradition of story telling spread throughout the world, several of Aesop’s Fables found their way from the West to the East. As Jelaluddin Rumi had himself been collecting similar stories, several of them were included in his late work the Masnavi. In more recent times, new translations of these have been undertaken by Coleman Barks, especially in his books on The Soul of Rumi and One-Handed Basket Weaving.

So the following is a selection of three poems. Two versions of the story of the friendship between a bear and a gardener: the first is Marianne Moore’s translation of La Fontaine’s “The Bear and the Garden-Lover” and the second one is Coleman Barks’ translation of “The Man with a Bear” by Rumi. The final selection is a short piece from Marianne Moore’s translations titled “The Fox and the Grapes.” The works of art by Gustave Doré, an Anonymous Persian Miniaturist, and François Chauveau.

The Bear and the Garden-Lover

“A bear with fur that appeared to have been licked backward

Wandered a forest once where he alone had a lair.

This new Bellerophon, hid by thorns which pointed outward,

Had become deranged. Minds suffer disrepair

When every thought for years has been turned inward.

We prize witty byplay and reserve is still better,

But too much of either and health has soon suffered.

No animal sought out the bear

In coverts at all times sequestered,

Until he had grown embittered

And, wearying of mere fatuity,

By now was submerged in gloom continually.

He had a neighbor rather near,

Whose own existence had seemed drear;

Who loved a parterre of which flowers were the core,

And the care of fruit even more.

But horticulturalists need, besides work that is pleasant,

Some shrewd choice spirit present.

When flowers speak, it is as poetry gives leave

Here in this book; and bound to grieve,

Since hedged by silent greenery to tend,

The gardener thought one sunny day he’d seek a friend.

Nursing some thought of the kind,

The bear sought a similar end

And the past just missed collision

Where their paths came in conjunction.

Numb with fear, how ever get away or stay here?

Better be a Gascon and disguise despair

In such a plight, so the man did not hang back or cower.

Lures are beyond a mere bear’s power

And this one said, ‘Visit my lair.’ The man said, ‘Yonder bower,

Most noble one, is mine; what could be friendlier

Than to sit on tender grass and share such plain refreshment

As native products laced with milk? Since it’s an embarrassment

To lack what lordly bears would have as daily fare,

Accept what if here.’ The bear appeared flattered.

Each found, as he went, a friend was what most mattered;

Before they’d neared the door, they were inseparable.

As confidant, a beast seems dull.

Best live alone if wit can’t flow,

And the gardener found the bear’s reserve a blow,

But conducive to work, without sounds to distract.

Having game to be dressed, the bear, as it puttered,

Diligently chased or slaughtered

Pests that filled the air, and swarmed, to be exact,

Round his all too weary friend who lay down sleepy—

Pests—well, flies, speaking unscientifically.

One time as the gardener had forgot himself in dream

And a single fly had his nose at its mercy,

The poor indignant bear who had fought it vainly,

Growled, ‘I’ll crush that trespasser; I have evolved a scheme.’

Killing flies was his chore, so as good as his word,

The bear hurled a cobble and made sure it was hurled hard,

Crushing a friend’s head to rid him of a pest.

With bad logic, fair aim disgraces us the more;

He’d murdered someone dear, to guarantee his friend rest.

Intimates should be feared who lack perspicacity;

Choose wisdom, even in an enemy.”1

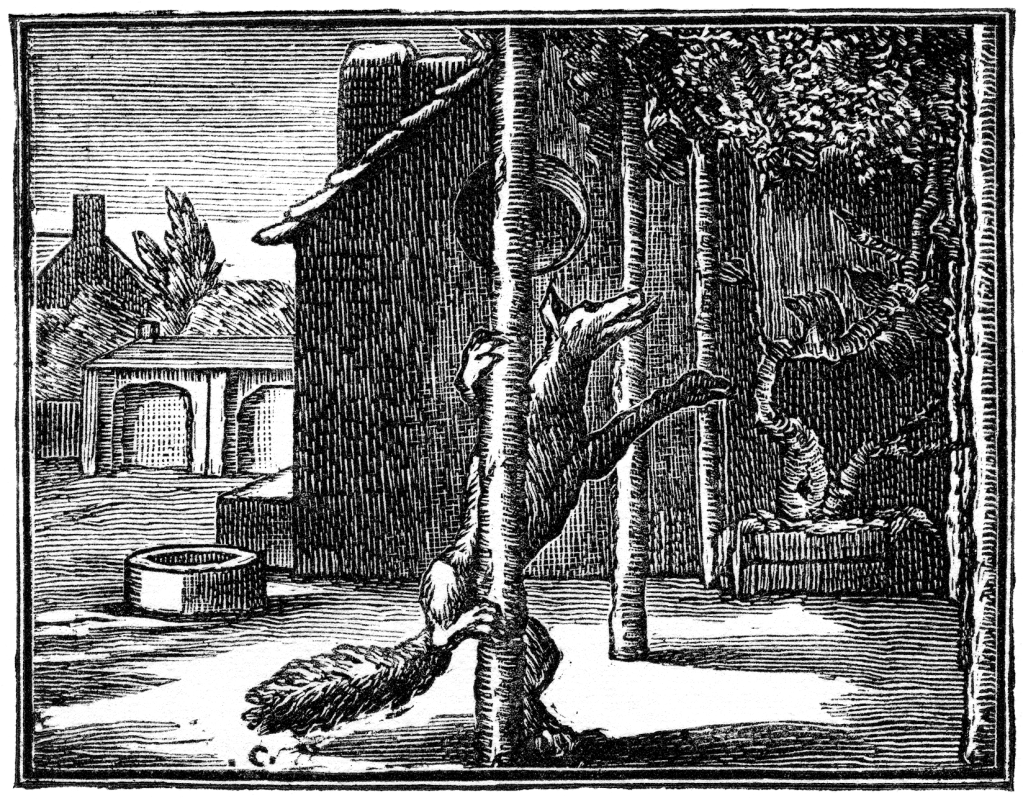

Jean de La Fontaine’s “L’Ours et l’amateur des jardins”

1868

Wood engraving

Public Domain

“The Man with a Bear”

“For the man who saved the bear

from the dragon’s mouth, the bear

became a sort of pet.

When he would lie down to rest,

the bear would stand guard.

A certain friend passed by,

‘Brother how did this bear

get connected to you?’

He told the adventure with the dragon,

and the friend responded,

‘Don’t forget

what your companion is. This friend

is not human! It would be better

to choose one of your own kind.’

‘You’re just jealous of my unusual helper.

Look at his sweet devotion. Ignore

the bearishness!’

But the friend was not convinced,

‘Don’t go into the forest

with a comrade like this!

Let me go with you.’

‘I’m tired.

Leave me alone.’

The man began imagining

motives other than kindness for his friend’s concern.

‘He has made a bet with someone

that he can separate me from my bear.’ Or,

‘He will attack me when my bear is gone.’

He had begun to think like a bear!

So the human friends went different ways,

the one with his bear into a forest,

where he fell asleep again.

The bear stood over him

waving the flies away.

But the flies kept coming back,

which irritated the bear.

He dislodged a stone from the mountainside

and raised it over the sleeping man.

When he saw that the flies had returned

and settled comfortably on the man’s face,

He slammed the stone down, crushing

to powder the man’s face and skull.

Which proves the old saying:

IF YOU’RE FRIENDS

WITH A BEAR,

THE FRIENDSHIP

WILL DESTROY YOU.

WITH THAT ONE,

IT’S BETTER TO BE

ENEMIES.”2

“Masnavi-i ma’navi” by Jalal al-Din Rumi

1663

Ink and pigments on thin laid paper

10 7/16” x 5 7/8”

The Walters Art Museum,

Baltimore, Maryland.

The Fox and the Grapes

“A fox of Gascon, through some say of Norman descent,

When stared till faint gazed up at a trellis to which grapes were tied—

Matured till they glowed with a purplish tint

As though there were gems inside.

Now grapes were what our adventurer on strained haunches chanced to crave

But because he could not reach the vine

He said, ‘These grapes are sour; I’ll leave them for some knave.’

Better, I think, than an embittered whine.”3

“Illustration for the Fables de La Fontaine, Volume 1”

1668

Burin engraving

Claude Barbin & Denys Thierry,

Paris, France

1 Moore, Marianne; Grace Schulman, ed.; The Poems of Marianne Moore, Viking Penguin; New York, New York; 2003; pp. 370-371.

2 Barks, Coleman; RUMI One-Handed Basket Weaving Poems on the Theme of Work; MAYPOP; Athens, Georgia; pp. 23-24.

3 Moore, Marianne; Grace Schulman, ed.; The Poems of Marianne Moore, Viking Penguin; New York, New York; 2003; p. 365.