At the Cincinnati Art Museum near the end of the summer of 2006 there was a special exhibition of paintings by the Irish painter Sean Scully titled “Wall of Light.” It originated at the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC, in late 2005 and included approximately eighty paintings and thirty works on paper including drawings, watercolors, and photographs.

One particular photograph of an old farm shack made from stacked stone featured a beautiful façade complete with light, shadow, texture: some of the very things that Scully looks at and draws from outside of his studio, in the real world. And certain writers have noted how the elements in Scully’s paintings are placed as if they were bricks or stones.

“Stone Shack End”

1994

Gelatin silver print

16” x 20”

Collection of the artist.

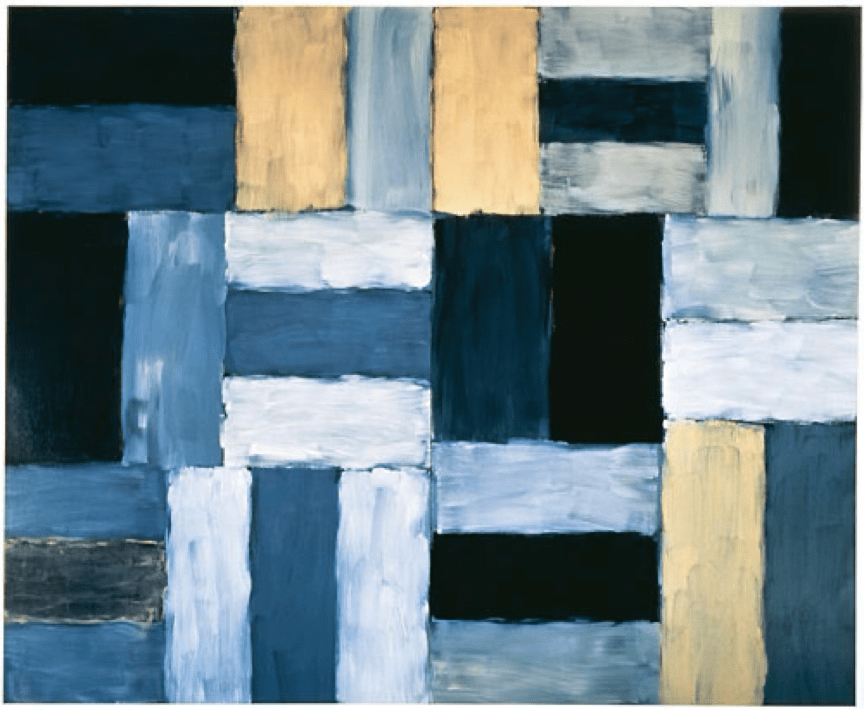

John Yau’s description of Scully’s painted surfaces is one example: “The rhythmic brushstrokes—ranging from feathery to matter-of-fact—and the layers of paint (running from thin to pasty) are visceral, even as light seeps through the interstices or flares where the slabs of caressed color don’t touch. The surface is neither uniform nor packed solid; it breathes. The bricks of color and the luminous spaces between them are equally important, with neither trumping the other.”1

“Wall of Light: Desert Night”

1999

Oil on canvas

108”x 132”

Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth

Fort Worth, Texas

Stephen Bennett Phillips, writing for the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC, has also observed: “Compositionally, within the Wall of Light series, Scully’s tendency has been to become increasingly asymmetrical and off-kilter. His longstanding focus on stripes—short ones in the case of the Wall of Lights paintings—can be compared with Giorgio Morandi’s lifelong study of a narrow range of still-life forms. In fact, Scully’s brick-like forms are directly analogous to blocks and voids that appear in Morandi’s still lifes.”2

“Still Life”

1953

Oil on canvas

8” x 15 1/8”

The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC.

In the book by John Yau titled Sean Scully: Night and Day, it seems to me that Yau is not just writing a curator’s statement, or a critical essay but going much further, as a poet would. Using sensitive descriptions of the paintings, along with insightful analysis, he arrives at a synthesis of lyrical and critical reflections on these works of art. Yau has, in essence, created an extended prose poem, whose subject is this series by Scully. The literary pieces that grow out of these paintings, following reflection, lead us to a new vision and understanding of these very pieces.

One summer John Yau and his family spent a week on the Dingle Peninsula in western Ireland. The local architecture especially attracted them, from the great Gallarus Oratory down to the many local stone barns and sheds. Later that year, Yau interviewed Sean Scully in preparation for his book on the subject of Night and Day. The writing on Scully’s work contained many references to these buildings and walls and analogies to the process of building up layers of paint as if they were bricks and stones.

“. . . the irregularly shaped stones had to be fitted together. In a way that is breathtaking and inspiring, the people who built the Gallarus Oratory made improvisation and necessity inseparable. A similar indivisibility animates Scully’s work.”3

“Scully builds his compositions out of what he calls ‘bricks’ of rich and often dusty color, but, like the anonymous stonemasons of the Oratory, is similarly committed to improvisation within the indispensable structures he discovers for himself. Whatever the inspiration for a painting might be—and these have ranged from specific landscapes seen in a particular light to a favorite novel and works of art—the tension between obligation and invention is central to Scully’s practice.”4

“Night and Day”

2012

Oil on aluminum

110” x 320”

Courtesy Cheim & Read, New York

“Night and Day is a combination of rhythm and dissonance, with the alternating dark and light bands introducing a rhythmic, percussive aspect into the viewer’s visual experience.”5

“Even as I take note of the repetition, and recognize the changing parameters of the stacked, horizontal bands, I become increasingly sensitive to the shifts and modulations in tonality spanning Night and Day. The dusty, dirty, pale grays evoke certain streets in large cities, foggy mornings, wintry skies, and frozen lakes. The darker gray bands—ranging from slate and to ash, interrupted by midnight black—conjure a changing nocturnal domain. Evocative of winter, especially in northern climates, where the sun appears briefly, if at all, Night and Day thrives in contradiction; it is chilly and soft, warm and aloof.”6

Amongst his own writings, the artist Sean Scully has offered several observations and descriptions of the work of other artists, especially Mark Rothko, Vincent van Gogh, and Giorgio Morandi. One example here, is Scully writing about Morandi: “Morandi paints like no other, before or since. His brushstroke is in complete philosophical agreement with the subject, the scale and the color of his paintings. It is expressive, though it is modest, and not so expressionistic as to disturb the senses of meditative silence that inhabits all his works.”7

“Still Life”

1953-54

Oil on canvas

26cm x 70cm

Museo di Arte Moderna e Contemporanea

di Trento e Rovereto, Giovanardi Collection.

1 Yau, John; Sean Scully: Night and Day; Cheim & Read; New York, New York; 2013; (unpaginated).

2 Phillips, Stephen Bennett, et. al.; Sean Scully: Wall of Light; The Phillips Collection; Washington, D.C. and Rizzoli International Publications; New York, New York; 2005; p. 43.

3 Yau, John; Sean Scully: Night and Day; Cheim & Read; New York, New York; 2013; (unpaginated).

4 Yau, John; Sean Scully: Night and Day; Cheim & Read; New York, New York; 2013; (unpaginated).

5 Yau, John; Sean Scully: Night and Day; Cheim & Read; New York, New York; 2013; (unpaginated).

6 Yau, John; Sean Scully: Night and Day; Cheim & Read; New York, New York; 2013; (unpaginated).

7 Ingleby, Florence, ed.; Sean Scully: Resistance and Persistence, Selected Writings; Merrell Publishers Limited; London and New York; 2006; p. 15.