Somehow in the course of events we have been led to believe that the ‘modern’ has come to mean only formalist abstraction and minimalism. A smaller and smaller world defined by a very tight description. There are however, several important modern writers and artists who have paid special attention to the details of modern life, seeing in them the larger world and how these details might speak to us.

SUNDAY NIGHT

“Make use of the things around you.

This light rain

Outside the window, for one.

This cigarette between my fingers,

These feet on the couch.

The faint sound of rock-and-roll,

The red Ferrari in my head.

The woman bumping

Drunkenly around the kitchen . . .

Put it all in,

Make use.”[i]

“Don’t forget when the phone was off the hook

all day, every day.”[ii]

“When, at 12:24, I look at the clock that isn’t running and it tells

the same time as the clock that is”[iii]

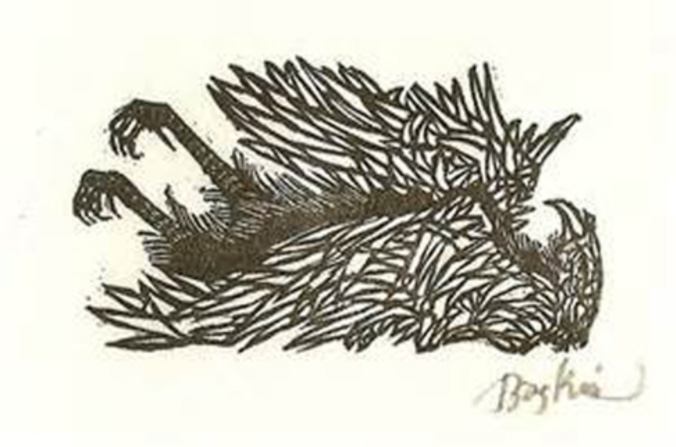

As we read the above observations, both Musa McKim and Raymond Carver look directly at the world surrounding us: a telephone lying off its hook, a broken alarm clock, a bag of sugar, or just the sun creating a glare on a sheet of white paper. Many of the same things that would catch the eye of an artist. The abstract form and shape of a grand piano, or the abstracted movement of a bird in space. All are examples of minimal imagery with maximum power that both poets and painters would employ.

Brancusi’s sculpture, straight out of a folk tradition, but unrecognzable to the Parisian elite, later became the sophisticated form that synthesized beauty, abstraction and content. There is the catch: abstraction and content. At first no one saw Brancusi’s pieces as birds, neither in space nor in flight. Today, however, they have become a symbol of just that.

“Bird in Space”

1928

Bronze

54” x 8 ½” x 6 ½”

Collection: Museum of Modern Art, New York

Not unlike the sculpture of Brancusi, the orchestral pieces of Igor Stravinsky synthesized classical music with jazz, folk and even the primal. Traditional painting had also gone through a similar synthesis of realism, cubism and pure plastic painting.

“Igor Stravinsky, New York City”

1946

Black & White Photograph

12 1/16” x 22 5/16”

National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC.

In the 1950’s and 60’s many young art students were taught by American abstract artists. Process and abstraction formed the content of most of the work at that time. But later, outside of academia, these artists were also confronted by the dilemma of what to do now? They were well versed in process, but struggled to find content. One artist however, set the most impressive example. Philip Guston at his Marlborough show in 1970 envisioned the end of one aspect of this process, and opened the gates and possibilities to new forms of imagery. Making use of the things around him.

By looking at certain details occurring in the world he single handedly opened the doors for himself, for poets, and later artists to come. These included Clarke Coolidge, Musa McKim, Raymond Carver, Robert Moskowitz, Elizabeth Murray, Susan Rothenberg and more.

“I thought I would never write anything down again. Then I put on my cold wristwatch.”[iv]

“I thought I would never write anything down again.”

(UNDATED)

Pen & ink drawing on paper

19” x 24”

The Estate of Musa Guston

In the mid 1960’s Robert Moskowitz produced a series of small paintings of a simple corner of a room. Quiet, minimal, very abstract and infused with a new sense of content and space. Where the simplest shape or form of a thing could clearly speak.

He would later take this process, including both personal and universal images, and juxtapose them in subtle but provacotive ways. A corner of the Flatiron Building, or the tops of the Empire State Building and the World Trade Towers, for example. A simplified assortment of visual images, not unlike the sparse and provacotive language used by Raymond Carver and Musa McKim.

“Untitled (Empire State)”

1980

Graphite and pastel on paper

106” x 31 1/4”

Collection: Mr. and Mrs. Robert K. Hoffman,

Dallas, Texas

“Talking about her brother Morris, Tess said:

‘The night always catches him. He never

believes it’s coming.’”[v]

“When on TV I see my sister in a bit part in an old movie”[vi]

“Three men and a woman in wet suits. The door to their motel room is open and they are watching TV.”[vii]

“And below in the street they are rattling the Coca-Cola bottles”[viii]

“Painting (For Duke Ellington)”

1977

Oil on canvas

90” x 75”

Collection of Mary and Jim Parton, Great Falls, Virginia

His Bathrobe Pocket Stuffed With Notes

“Duke Ellington riding in the back of his limo, somewhere

in Indiana. He is reading by lamplight. Billy Strayhorn

is with him, but asleep. The tires hiss on the pavement.

The Duke goes on reading and turning the pages.”[ix]

[i] Carver, Raymond; “Sunday Night,” A New Path to the Waterfall; The Atlantic Monthly Press; New York, New York; 1989; p. 53.

[ii] Carver, Raymond; “His Bathrobe Pocket Stuffed With Notes,” A New Path to the Waterfall; The Atlantic Monthly Press; New York, New York; 1989; p. 66.

[iii] McKim, Musa; Alone With the Moon; The Figures; Great Barrington, Massachusetts; 1994; p. 105.

[iv] McKim, Musa; Alone With the Moon; The Figures; Great Barrington, Massachusetts; 1994; p. 121.

[v] Carver, Raymond; “His Bathrobe Pocket Stuffed With Notes,” A New Path to the Waterfall; The Atlantic Monthly Press; New York, New York; 1989; p. 64.

[vi] McKim, Musa; Alone With the Moon; The Figures; Great Barrington, Massachusetts; 1994; p. 105.

[vii] Carver, Raymond; “His Bathrobe Pocket Stuffed With Notes,” A New Path to the Waterfall; The Atlantic Monthly Press; New York, New York; 1989; p. 65.

[viii] McKim, Musa; Alone With the Moon; The Figures; Great Barrington, Massachusetts; 1994; p. 105.

[ix] Carver, Raymond; “His Bathrobe Pocket Stuffed With Notes,” A New Path to the Waterfall; The Atlantic Monthly Press; New York, New York; 1989; p. 66.