“The colour blue offers a multiplicity of remarkable characteristics to the observing eye and to the reflective mind alike. It is the only colour which can be seen as a close neighbor to and essentially akin to both dark and light, almost black in the night and almost white at the horizon by day; and it is also the colour of shadows on snow. It can darken, it can obscure, it may float to and fro like a mist, dimming reality with sadness and concealing truth…. By contrast light blue is the colour of loyalty and ecstasy—‘true blue’ for example….”1

This description is from a remarkable study on Paul Cézanne by the German art historian Kurt Badt. Cézanne of course pushed the use of color and structure to new limits in all of his work and so many of the younger artists migrating to Paris at the beginning of the 20th Century soon became aware of this, including Pablo Picasso.

“Self Portrait”

1901

Oil on canvas

81 cm x 60 cm

Picasso Museum, Paris

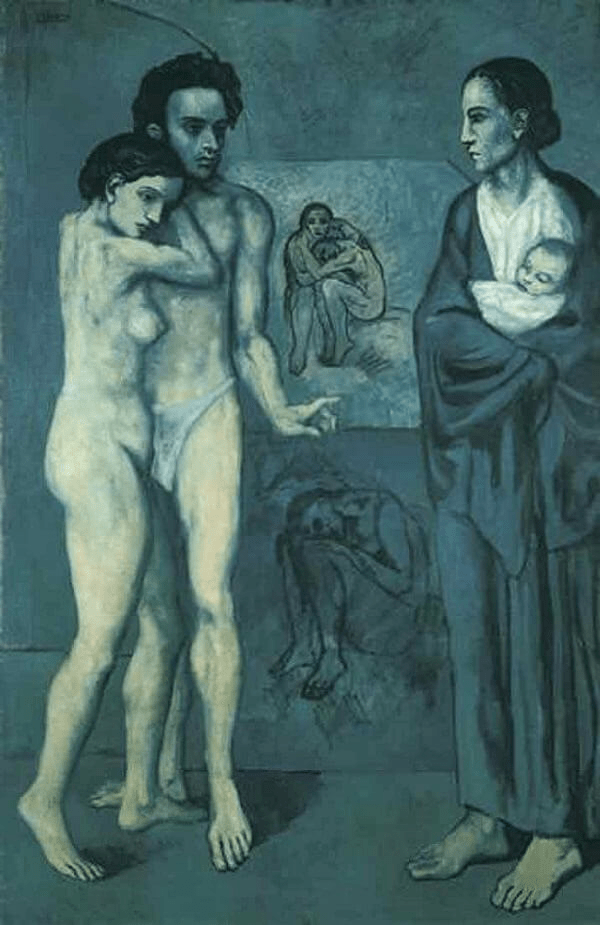

For Picasso, this became one of the most important attributes to his early paintings. Alone and isolated as many artists found themselves in Paris at that time, it was inevitable that a certain melancholy would set in. This was intensified by the sudden death of one of his dear friends, Casagemas. The psychological range of the color blue became an important element in his search for a way out of his situation. Using local residents, not traditional artist’s models, he began to paint this series from 1901 through 1904. His portrait of Casagemas was painted as a tribute in 1901, and was included again as the male figure in “La Vie” from the Cleveland Museum of Art in 1903.

Along with his description of the color blue, Kurt Badt also has mentioned the psychology of this color, even referring to it emotionally as ‘the blues’ as we might assume. For Picasso, this was a turning point.

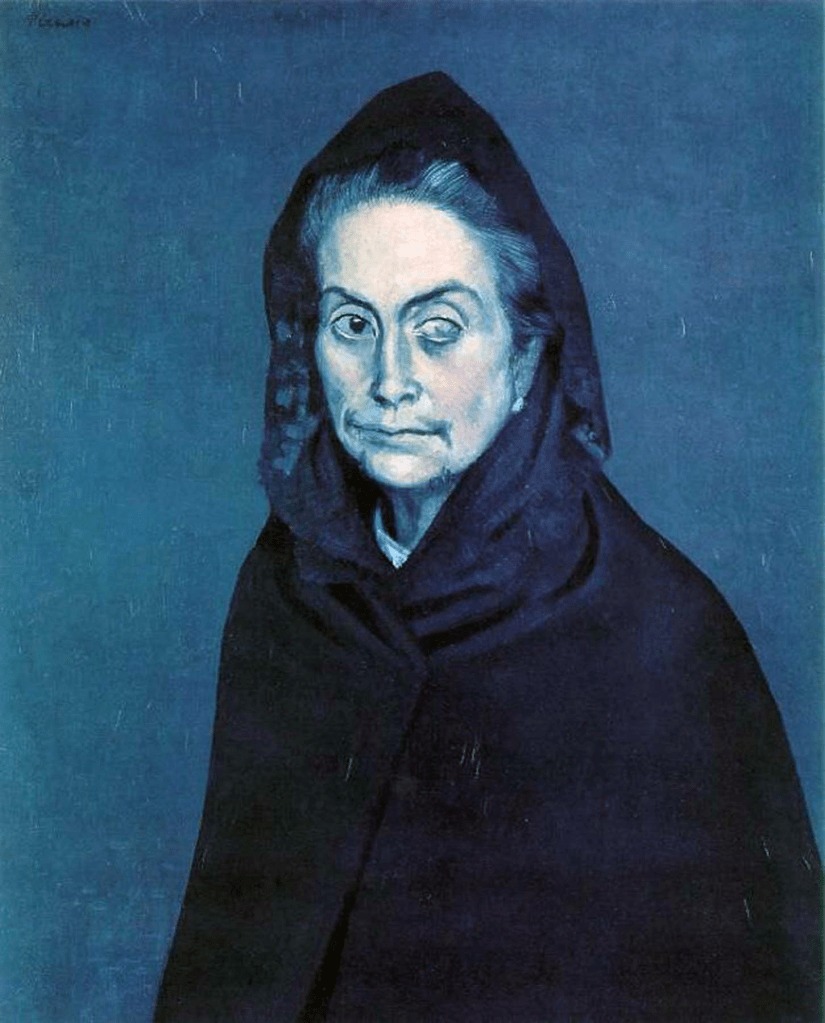

“La Celestina”

1904

Oil on canvas

70 cm x 56 cm

Musee Picasso, Paris

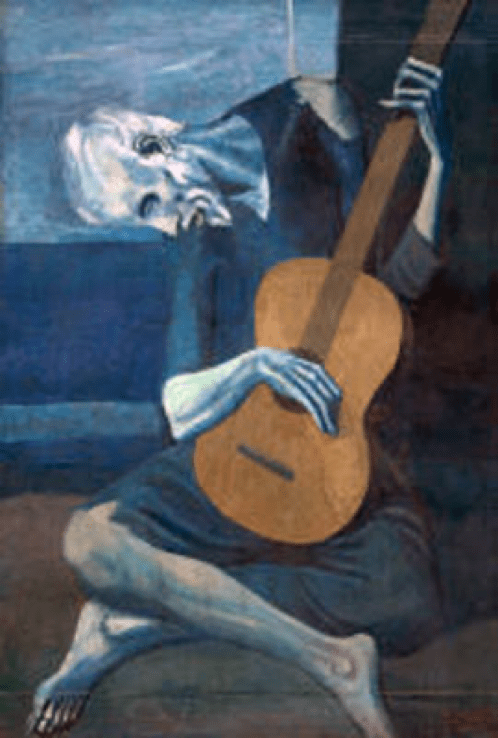

Whether it was a half blind woman in the street, a procuress named Celestina from a Spanish tragicomedy of 1499, or a totally blind man having his evening dinner, the people, their poses, and their color are simultaneously expressing a set of emotions and questions for the viewer. Add to these images, the portrait of “The Old Guitarist” from the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, and we have more questions regarding life during this time period.

“The Blind Man’s Meal”

1903

Oil on canvas

37 1/2” x 37 1/2”

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The musician, with his head bent over his instrument, with the weight of blue pressing down on his shoulder, we follow the line of his arm downward to the elbow and across to his hand strumming the guitar. And then up the neck of this guitar, to his fingers holding steady on the chords, and then across to his other shoulder, through his own neck and back to his dazed expression: a full compositional circle. This resulted of course, in one of the most important modern examples of the ekphrastic tradition, Wallace Stevens’ “The Man with the Blue Guitar.”

“The man bent over his guitar,

A shearsman of sorts. The day was green.

They said, ‘You have a blue guitar,

You do not play things as they are.’

The man replied, ‘Things as they are

Are changed upon the blue guitar.’

And they said to him, ‘But play, you must,

A tune beyond us, yet ourselves,

A tune upon the blue guitar,

Of things exactly as they are.’”2

“I cannot bring a world quite round,

Although I patch it as I can.

I sing a hero’s head, large eye

And bearded bronze, but not a man,

Although I patch him as I can

And reach through him almost to man.

If a serenade almost to man

Is to miss, by that, things as they are,

Say that it is the serenade

Of a man that plays a blue guitar.”

“The Old Guitarist”

1903–1904

Oil on panel 48 3/8” x 32 1/2”

The Art Institute of Chicago

So, we have a set up between the artist and the audience: the artist saying that things are changed upon the blue guitar, while the audience insists upon a tune of things exactly as they are!

Stevens starts with this guitarist from the Blue Period but soon goes on to other thoughts, not descriptive but reflective: “A tune beyond us as we are….”3 and ventures into the modern world of painting and poetry. He has to touch upon descriptions of general life and the accompanying dilemmas of 20th century artists. This then continues through several of the later sections of this poem. As Glen MacLeod mentioned in Wallace Stevens and Modern Art, he fuses references to Picasso with more general observations to modern life and a sense of contemporary surrealism, a kind of “…permissible imagination.”4

“A tune beyond us as we are,

Yet nothing changed by the blue guitar;

Ourselves in tune as if in space,

Yet nothing changed, except the place

Of things as they are and only the place

As you play them on the blue guitar,

Placed, so, beyond the compass of change,

Perceived in a final atmosphere;

For a moment final, in the way

The thinking of art seems final when

The thinking of god is smoky dew.

The tune is space. The blue guitar

Becomes the place of things as they are,

A composing of senses of the guitar.”5

“La Vie”

1903

Oil on canvas

197 cm x 129 cm

The Cleveland Museum of Art,

Cleveland, Ohio

“The world washed in his imagination,

The world was a shore, whether sound or form

Or light, the relic of farewells,

Rock, of valedictory echoing,

To which his imagination returned,

From which it sped, a bar in space,

Sand heaped in the clouds, giant that fought

Against the murderous alphabet:

The swarm of thoughts, the swarm of dreams

Of inaccessible Utopia.

A mountainous music always seemed

To be falling and to be passing away.”6

“Is this picture of Picasso’s, this ‘hoard

Of destructions’, a picture of ourselves,

Now, an image of our society?”7

1 Badt, Kurt; The Art of Cezanne; University of California Press; Berkeley and Los Angeles; 1965; pp. 58-59.

2 Stevens, Wallace; “The Man With The Blue Guitar” Collected Poetry and Prose; The Library of America; New York, New York; 1997; Section I, p. 135.

3 Stevens, Wallace; “The Man With The Blue Guitar” Collected Poetry and Prose; The Library of America; New York, New York; 1997; Section VI, p. 137.

4 MacLeod, Glen; Wallace Stevens and Modern Art: From the Armory show to Abstract Expressionism; Yale University Press; New Haven and London; 1993; p. 197.

5 Stevens, Wallace; “The Man With The Blue Guitar” Collected Poetry and Prose; The Library of America; New York, New York; 1997; Section VI, p. 137.

6 Stevens, Wallace; “The Man With The Blue Guitar” Collected Poetry and Prose; The Library of America; New York, New York; 1997; Section XXVI, pp. 146-147.

7 Stevens, Wallace; “The Man With The Blue Guitar” Collected Poetry and Prose; The Library of America; New York, New York; 1997; Section XV, p. 141.