It is a monstrous painting. Huge when first encountered in the galleries of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, approximately seven feet high and eight feet across, impossible to be taken in all at once. Cezanne worked on this subject through many years and versions, always searching for the solution he had imagined.

“The Large Bathers”

1900-1906

6’ 10 7/8” x 8’ 2 3/4”

Oil on canvas

Philadelphia Museum of Art

We can see from several smaller studies how Cezanne’s ideas developed and grew over time. Two or three figures in one, three to five figures in another, numerous combinations and variations. This work was really important to Cezanne, but it was even more important to artists who followed him. Significantly amongst those in later generations were both Henry Moore and Henri Matisse. Each of them had actually owned smaller versions of Cezanne’s “Bathers.”

“Three Bathers”

c. 1875

Oil on canvas

12” x 13”

The Henry Moore Foundation

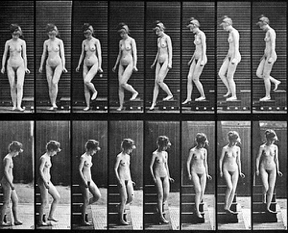

“I now own a small Cezanne Bathers painting, and in talking about it to friends, I have often said, ‘look what a romantic idea Cezanne had of women,’ and, ‘how fully he realised (sic) the three-dimensional world.’ I felt that I could easily make sculptures of his figures.”

“Stephen Spender in a letter to me said, ‘your idea of showing that you could make sculptures of the Cezanne figures is fascinating. Why don’t you do it?’ Soon after his letter, I felt like proving it, and modeled each of the three figures in plasticine, taking about an hour in all. My idea was to show their existence completely in space, and perhaps to photograph them or make drawings, as it were, from behind the picture, showing them from all sides and demonstrating that they had been conceived by Cezanne in full three dimensions.”

“Three Bathers—After Cezanne”

1978

Bronze

1. 30.5 cm. (length 12”)

The Henry Moore Foundation

“I enjoyed the whole of this experience. I had thought I knew our ‘Bathers’ picture completely, having lived with it for twenty years. But this exercise—modelling the figures and drawing them from different views—has taught me more than any amount of just looking at the picture.”

“This example shows that working from the object—modelling or drawing it—makes you look much more intensely than ever you do if you just look at something for pleasure.”[i]

There is a popularly held misconception that artists are bad writers, although to this day we are constantly required to submit an “artist’s statement” for any and every thing we do. However, from the number of letters written back and forth amongst artists, from entries written in their notebooks and journals, and explanations that many curators require from the artists they are celebrating, it is clear that visual artists are also very articulate with regards to the written word.

Here are two examples, from Henry Moore above and Henri Matisse below, reflecting their personal thoughts and observations on several versions of Paul Cezanne’s “Bathers.” They write clearly and straightforwardly regarding these paintings, all the while rediscovering how important Cezanne’s work actually was.

Henry Moore has worked with the pure plastic sense of both painting and sculpture and the process of articulating form in space. This is evident in all of his later work, and his many figurative pieces.

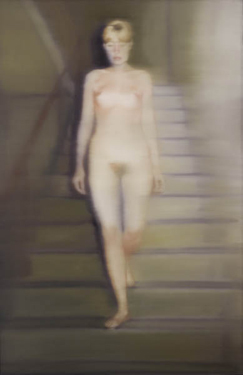

Henri Matisse is drawing from the Cezanne and searching for a more complete realization of a composition as seen over several years. Amongst several examples this would lead to his great “Bathers by a River” of 1917 at the Art Institute of Chicago.

“Bathers by a river”

1909-1917

Oil on canvas

102 1/2” x 154 3/16”

Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection

The Art Institute of Chicago

In 1899 Henri Matisse purchased “Three Bathers” by Cezanne from the Parisian art dealer Vollard. He kept it in his possession until 1936 when he donated it to the Petit Palais in Paris. On 10 November 1936 he wrote this letter to Raymond Escholier, the director of the museum:

“Allow me to tell you that this picture is of the first importance in the work of Cezanne because it is a very dense, very complete realization of a composition that he carefully considered in several canvases which, though now in important collections, are only the studies that culminated in this work.”

“In the thirty-seven years I have owned this canvas, I have come to know it quite well, though not entirely, I hope; it has sustained me morally in the critical moments of my venture as an artist; I have drawn from it my faith and my perseverance; for this reason, allow me to request that it be placed so that it may be seen to its best advantage. For this it needs both light and adequate space. It is rich in color and surface, and seen at a distance it is possible to appreciate the sweep of its lines and the exceptional sobriety of its relationships.”

“I know that I do not have to tell you this, but nevertheless I think it is my duty to do so; please accept these remarks as the excusable testimony of my admiration for this work which has grown increasingly greater ever since I have owned it. Allow me to thank you for the care that you will give it, for I hand it over to you with complete confidence. . . .”[ii]

“Three Bathers”

1879-1882

Oil on canvas

55 cm. x 52 cm.

Gift of Henri Matisse to the Petit Palais,

the City Museum of Paris in 1936

[i] Wilkinson, Alan, ed; Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations; University of California Press; Berkeley and Los Angeles; 2002; pp. 307-309.

[ii] Flam, Jack; Matisse on Art; University of California Press; Berkeley, Los Angeles and London; 1995; p. 124.