So many wars, the Eighty Years War and the Franco-Dutch War among them. During a peaceful interlude a pet goldfinch was waiting patiently to be painted. Later, the explosion of the powder magazine in Delft and the death of Carel Fabritius. And that beautiful spot of yellow on the rooftops of the city of Delft, as well as the nearby shadows on the Oude Kerk and the light on the Nieuwe Kerk in the “View of Delft.” The Nieuwe Kerk where Johannes Vermeer was baptized and the resting place for William of Orange.

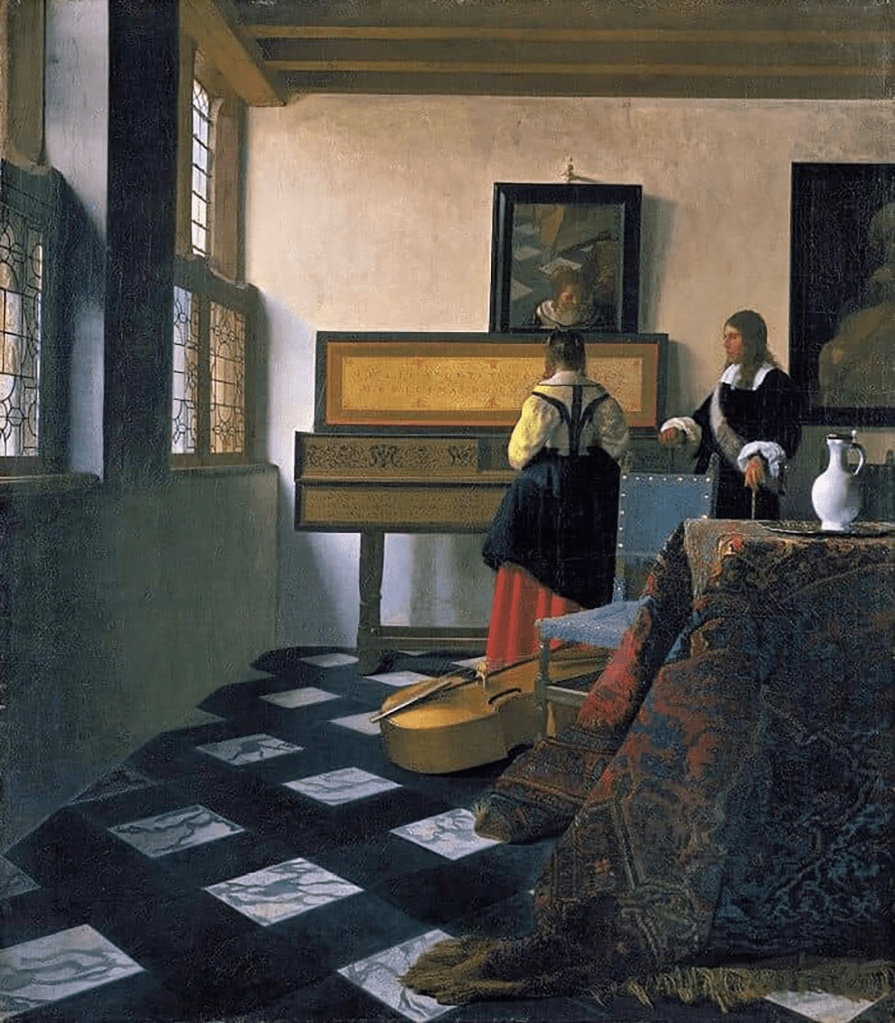

“The Music Lesson”

1662-1664

Oil on canvas

73.3cm x 64.5cm

The Royal Collection

London, United Kingdom

Such an important poet in his own right, Robert Bly was also a significant translator of the work of other poets. He published for the first time, many European and South American poets, and his translations range from Goethe, Hölderlin, Kabir, Rilke, Rumi, Ghalib and now to Tomas Tranströmer.

In his introduction to this translation of Tranströmer’s work, Bly mentions, a couple of times “. . . something approaching over a border. . . .”1 or “. . . the noise begins over there, on the other side of the wall. . . .”2 A kind of literary searching, I think, as both a poet and translator. Something beyond, but something that we cannot exactly put our finger on, in order to break through, either a border or a wall.

Vermeer

“It’s not a sheltered world. The noise begins over there, on the

other side of the wall

where the alehouse is

with its laughter and quarrels, its rows of teeth, its tears, its

chiming of clocks,

and the psychotic brother-in-law, the murderer, in whose

presence everyone feels fear.

The huge explosion and the emergency crew arriving late,

boats showing off on the canals, money slipping down into

pockets—the wrong man’s—

ultimatum piled on ultimatum,

wide-mouthed red flowers whose sweat reminds us of

approaching war.

And then straight through the wall—from there—straight into

the airy studio

and the seconds that have got permission to live for centuries.

Paintings that chose the name: The Music Lesson

or A Woman in Blue Reading a Letter.

She is eight months pregnant, two hearts beating inside her.

The wall behind her holds a crinkly map of Terra Incognito.

Just create. An unidentifiable blue fabric has been tacked to

the chairs.

Gold-headed tacks flew in with astronomical speed

and stopped smack there

as if they had always been stillness and nothing else.

The ears experience a buzz, perhaps it’s depth or perhaps

height.

It’s the pressure from the other side of the wall,

the pressure that makes each fact float

and makes the brushstroke firm.

Passing through walls hurts human beings, they get sick from

it,

but we have no choice.

It’s all one world. Now to the walls.

The walls are a part of you.

One either knows that, or one doesn’t; but it’s the same for

everyone

except for small children. There aren’t any walls for them.

The airy sky has taken its place leaning against the wall.

It is like a prayer to what is empty.

And what is empty turns its face to us

and whispers:

‘I am not empty, I am open.’”3

“Woman in Blue Reading a Letter”

1662-1664

Oil on canvas

46.5cm x 39cm

Rijksmuseum,

Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Later in life Tomas Tranströmer suffered a stroke that left his right side paralyzed, leading to difficulties in both writing and his piano playing. Several of his friends and colleagues, musicians and composers, set about composing piano pieces to be played only by the left hand, and sent them directly to him.4

Tranströmer’s imagery is so clear that we believe in its reality and in his imagination. As when he drew out a piano key-board on the kitchen tabletop in order to silently practice his music: “I played on them, without a sound. Neighbors came by to listen!”5

1 Tranströmer, Tomas; Translated by Robert Bly; The Half-Finished Heaven; Graywolf Press; Saint Paul, Minnesota; 2001; p. xviii.

2 Tranströmer, Tomas; Translated by Robert Bly; The Half-Finished Heaven; Graywolf Press; Saint Paul, Minnesota; 2001; p. xviii.

3 Tranströmer, Tomas; Translated by Robert Bly; The Half-Finished Heaven; Graywolf Press; Saint Paul, Minnesota; 2001; pp. 87-88.

4 Tranströmer, Tomas; Translated by Robert Bly; The Half-Finished Heaven; Graywolf Press; Saint Paul, Minnesota; 2001; p. xxi.

5 Tranströmer, Tomas; Translated by Robert Bly; The Half-Finished Heaven; Graywolf Press; Saint Paul, Minnesota; 2001; p. xx.