My friend and colleague, Brett Waller, Director Emeritus of the Indianapolis Museum of Art, used to always mention to students and visitors that art museums were the birth-right of artists: explaining that historically, when many royal and private collections were first opened to the public as museums, they were linked to the local art academies and schools.

Artists such as Paul Cézanne and Alberto Giacometti both were sensitive to the importance of museums and their collections. It was Cézanne who stated many times that “. . . it was his ambition ‘to do Poussin again after nature’ and that he wanted to make of Impressionism ‘. . . something solid and enduring like the art of the museums.’”1

In his Sketchbook of Interpretive Drawings Alberto Giacometti shows us both the range and depth of how he looked at the great art of museums: “I began to copy long before even asking myself why I did it, probably in order to give reality to my predilections, much rather this painting here than that one there, but for many years I have known that copying is the best means for making me aware of what I see, the way it happens with my own work; I can know a little about the world there, a head, a cup, or a landscape, only by copying it.”2

“Study after Pieter Breughel’s Hunters in the Snow”

c. 1952

Ballpoint pen on paper

8 1/4” x 11 1/2”

Annette and Alberto Giacometti Foundation,

Paris and Zurich

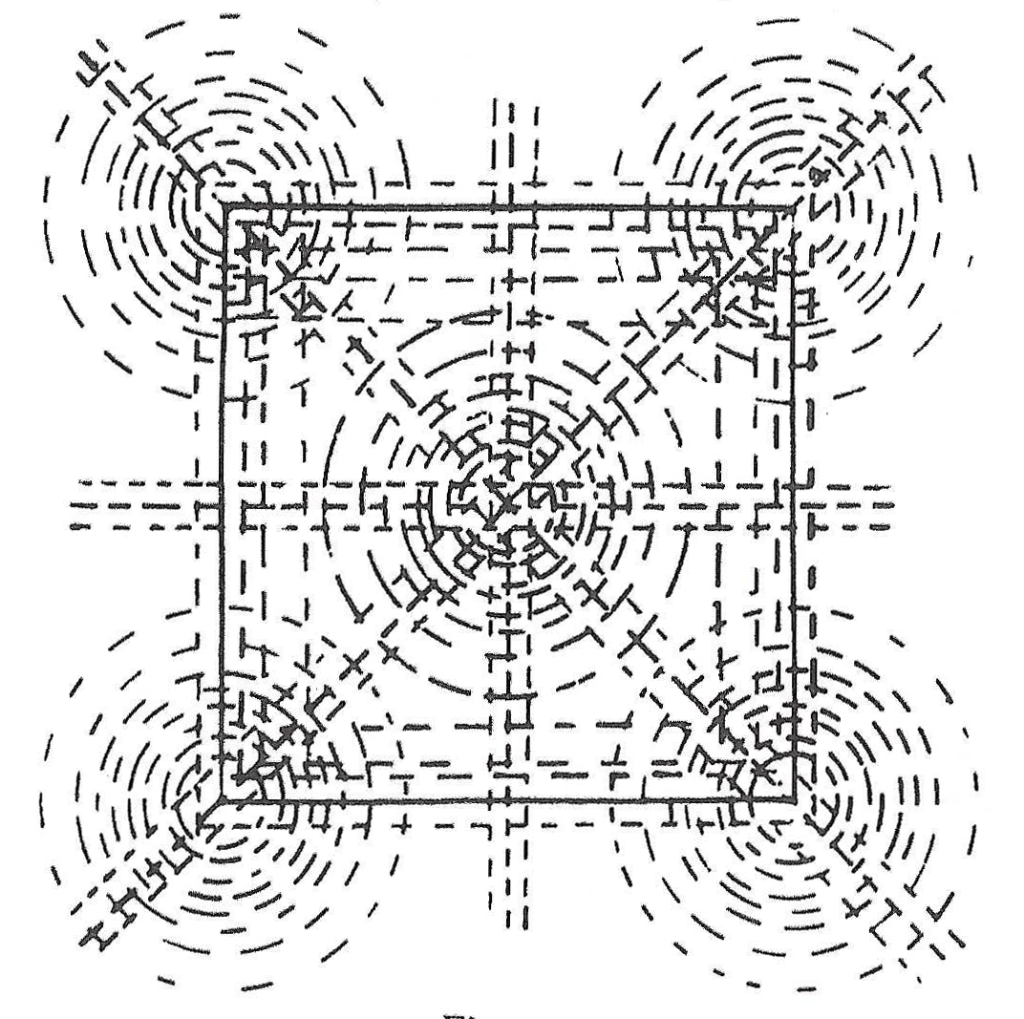

Through the writings of Rudolph Arnheim we have known of the ascending and descending angles and movements through out a painting.3 Also, we understand kinetic and haptic space as it runs through a work of art, leading our eye and mind through this very space.

“Structural Map” (Figure 3, p. 4)

Art and Visual Perception

1971

Whether it is a snow covered hill leading us downward from the center left to the bottom right of the painting, or the path that the hunters are taking from the lower left upward into the center, or even the complimentary angles of the magpie gliding above the distant landscape and holding the upper part of the composition, we can feel the structural movement throughout.

It is this seeing, and experiencing of the thing that is most important, and this of course is exactly what William Carlos Williams achieved with this great painting “The Hunters in the Snow.”

“The Hunters in the Snow”

1565

Oil on wood panel

46” x 63 3/4”

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

The Hunters in the Snow

“The over-all picture is winter

icy mountains

in the background the return

from the hunt it is toward evening

from the left

sturdy hunters lead in

their pack the inn-sign

hanging from a

broken hinge is a stag a crucifix

between his antlers the cold

inn yard is

deserted but for a huge bonfire

that flares wind-driven tended by

women who cluster

about it to the right beyond

the hill is a pattern of skaters

Breughel the painter

concerned with it all has chosen

a winter-struck bush for his

foreground to

complete the picture . . ”4

1 Chilvers, Ian, & John Glaves-Smith; A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art; Oxford University Press; Oxford, United Kingdom; 2009; p. 132.

2 Carluccio, Luigi; Giacometti: A Sketchbook of Interpretive Drawings; Harry N. Abrams, Inc.; New York, New York; 1967; p. xi.

3 Arnheim, Rudolf; Art and Visual Perception: A Psychology of the Creative Eye; University of California Press; Berkeley and Los Angeles; 1971; p. 4.

4 Williams, William Carlos; Pictures from Brueghel and other poems; New Directions Publishing Corporation; New York, New York; 1967; p. 5.