From Grand Rapids, Michigan to Baltimore, Maryland, the poet Patricia Clark is always searching for artists to study, and to be inspired by. In the last couple of years she has visited the work of two such artists. A newly installed sculpture by Deborah Butterfield on a rooftop balcony at Grand Valley State University at its Downtown Campus. And a few months later, on a trip to Baltimore, a pilgrimage of sorts to the Joan Mitchell Retrospective Exhibition at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

Just last year, 7 September 2023 to be exact, I attended a reading by Patricia Clark at the Poetry on Brick Street Series in Zionsville, Indiana. It was there, reading from a selection of her latest work, that I heard her read two new works, these ones on Deborah Butterfield and Joan Mitchell.

“Weeds”

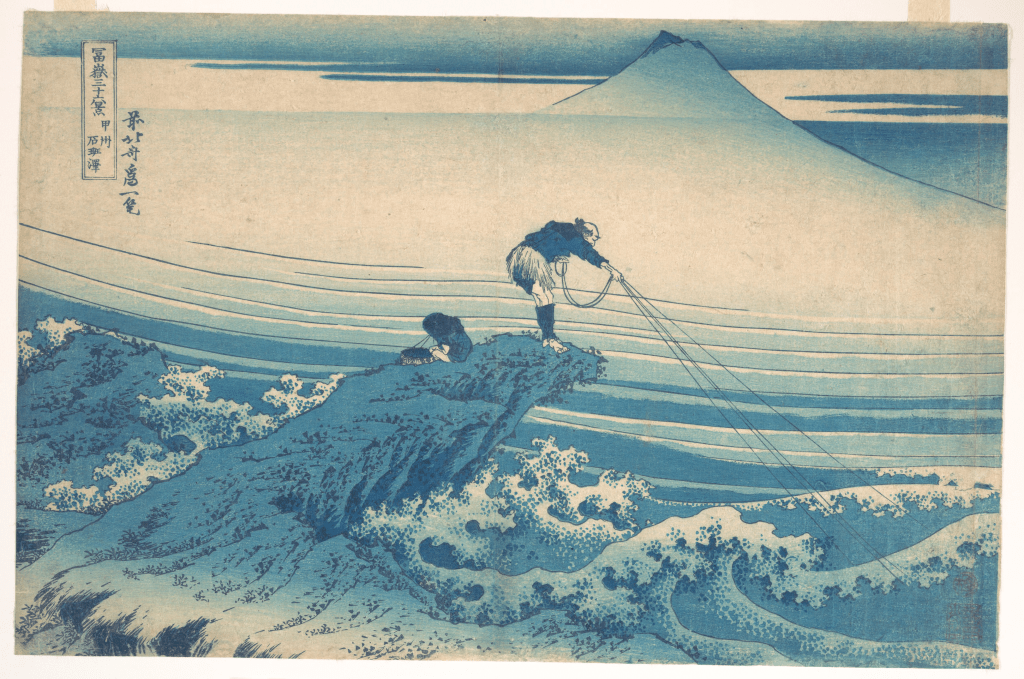

Installation view:

Joan Mitchell Retrospective Exhibition,

Baltimore Museum of Art,

2022

Situated in a prairie like setting at the Meijer Gardens and Sculpture Park in Grand Rapids is an isolated crazing horse by Deborah Butterfield1. It has a natural like stance and bend to its neck, standing in this open space. Further downtown, in fact near the very center of the city and elevated to the top of a Grand Valley State University classroom building, is another one of these pieces.

“Cabin Creek”

1999

Bronze

88” x 122.5: x 30.5”

Meijer Sculpture Garden and Park

Grand Rapids, Michigan

Char: Above the City

–for Nathan, Joel, and Alison

“On a rooftop downtown at the edge

of the building where they’ve planted succulents

stands a horse blackened by fire

called Char by its maker Deborah Butterfield.

The artist scoured a smoky ravaged forest

in California, picking up branches, limbs,

burnt saplings, then brought these to her studio

where she fashioned them into the shape of a horse.

During the process, taking weeks, Butterfield often dreams

of horses. This one grazing in a meadow

where red-tipped grass waved against its belly, seeds

catching in its long tail. Horse has become the artist’s

mirror self, a dream figure made manifest.

After the studio, a foundry, a way to cast

wood into metal, finally pouring

bronze for the final sculpture. The workers made marks

in metal to resemble wood, adding a patina black

as night sky. Char looks east into clouds

above our city, ignoring for past weeks

the haze from Canada wildfires, not pricking

its ears in terror or flipping its tail.

Char is more skeleton than mass, negative space

allowing us to glimpse what’s been ruined and where

we stand, on the edge, barely able to breathe.”2

“Char”

2021

Bronze

82.5″ x 102.5″ x 33″

Center for Interprofessional Health,

Grand Valley State University,

Grand Rapids, Michigan

In the Spring of 2019 I visited the Baltimore Art Museum in order to see the Joan Mitchell Retrospective3. It was the first time I had returned to Baltimore in so many years and certain sites were hard to remember. We arrived early, way before our scheduled entry time, not crowded at all so the guards waved us right on in. When I mentioned this to Patricia Clark later, back in the Mid-West, she stated that she and her husband Stanley Krohmer, who had also studied in Baltimore, were planning a very similar trip, and specifically to see the Joan Mitchell Retrospective.

One really important element to all of Mitchell’s work is her affinity with other artists and poets of her generation. Several of her paintings have inspired writers and writers have inspired her in both her paintings and her poem pastels.

These include James Schyler, Eileen Myles, Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery. Below is Patricia Clark’s poem in response to this exhibition.

Painter Joan Mitchell Pulls Me Up

“What was in the air was leaf-fall, the rot

of the year’s perennials and annuals, stems

and blossom ends done for, going back to earth.

I couldn’t move for being caught by the suck

of quicksand, a clump of blue feathers smacked

on a window from a hit. Here I am on a cold Friday

and to my amazement the painter Joan

Mitchell reaches for me, from her oil

on canvas, a diptych called Weeds,

grabbing a hold of me, saying ‘Here,

take my hand!’ There’s something about

her seeming riot of marks that’s giving

a calming and cooling effect. It’s cobalt blue,

orange, tawny, and flecked with white,

even a spot or two of sage, and I see

the trail-side at Huff Park with tall

teasel, Queen Anne’s lace, and a waving

frond of goldenrod or a flat-topped

white aster. Each year I’m caught watching

this awakening starting up in early spring,

a mere sprout or two at first, then

climbing, growing, a stem hoisting itself up

all season till it’s five feet high,

shedding petals, pollen and seeds. Not

a riot at all, a cyclic process of

great determination, genetics, chance . . .”

“Weeds”

1976

Oil on canvas,

110 1/2” x 157 1/2”

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

Washington, DC.

“. . . weather, sunlight, rain. Right now,

I’m bowing to the botanical display and to two

canvasses of supreme order, remembering

our visit to the Baltimore Art Museum, August,

standing in front of the actual paintings,

work as sturdy and wrought

as any palace. Then we went walking off

in a pack for lunch, having salad and Chesapeake oysters

on the half-shell along with a crisp

citrus tasting wine. Good friends, fellow

artists, a couple more hands to pull me

out of quicksand. Where do we turn, lost

on that trail, or sinking? The Baltimore light

was pure lemon as we strolled through

the galleries pointing, talking, saying

look at that magenta, violet, sage, her vision,

her ability to make these marks. The gleam of it

lasting as long as the light, what we call a day.”4

1 Kuspit, Donald, and Marcia Tucker; Horses: The Art of Deborah Butterfield; Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida, and Chronicle Books, San Francisco, California; 1992.

2 Clark, Patricia; “Char;” The Superstition Review; Arizona State University; Issue 32; Fall 2023.

3 Roberts, Sarah, and Katy Siegel, eds.; Joan Mitchell; Baltimore Museum of Art and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Yale University Press, New Haven and London; 2020.

4 Clark, Patricia; “Painter Joan Mitchell Pulls Me Up;” Nelle; University of Alabama at Birmingham; Issue 7; 2024.