“The Equestrienne”

1931

Oil on canvas

100 x 80.8 cm.

The Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

[i] Ferlinghetti, Lawrence; A Coney Island of the Mind; New Directions Publishing Corporation; New York, New York; 1958; p. 29.

“‘Listen,’ said Polly, ‘what’s that?’

The cataloguing team was walking back from lunch. Titus stopped in the west cloister and looked up at the windows of the Dutch Room. ‘I didn’t know there was a concert up there this afternoon.’

‘Concert?’ said Aurora, frowning. ‘What concert?’

‘Don’t you hear it?’ said Polly. ‘It’s nice. Really nice.’

‘But it’s Wednesday,’ said Aurora. ‘Concerts are Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Sundays.’

‘Maybe we’d better take a look,’ said Titus. With Polly at his heels, he hurried up the stairs.

‘Don’t be silly, Titus,’ Aurora called after them. ‘There isn’t any music. I don’t hear a thing.’

“But as Titus and Polly reached the top of the stairs, it was plainly audible to both of them, plangent notes from some sort of harpsichord, a threadlike soprano voice running softly down a scale to the plucked accompaniment of a guitar.

‘It’s probably for some special visit,’ said Titus, striding along the corridor. ‘I didn’t know one was scheduled for today. I must have forgotten.’

But there was no trio of musicians in the Dutch Room, no milling throng of polite guests. And the music had stopped.’”[i]

This is how the writer Jane Langton described one of a series of strange events occurring in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Later, music would also be heard coming from the Early Italian Room, from the Spanish Cloister, and finally from the Chinese Loggia. A “sympathetic displacement of noises” it was suggested.[ii] All of this and other strange happenings, including a murder, occurred in her fictional account of this museum in Boston.

One of the first major purchases by Isabella Stewart Gardner for her collection was Johann Vermeer’s “The Concert.” She accomplished this at an auction in Paris in 1892 and it later became one of the highlights of this important and personal collection.

Unfortunately, we know of it today as one of the 13 pieces that were stolen from the Gardner by intruders dressed in security guard’s uniforms in 1990 and never recovered. The placement of objects throughout the museum is strictly enforced and the current empty frames illustrate the absence of these treasures.

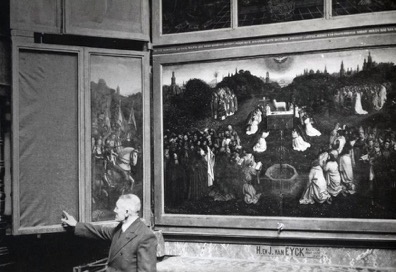

This might remind us of a similar mystery occurring 56 years earlier and on the other side of the Atlantic. A bungling Dutch constabulary spent the evening looking closer at a theft in a cheese shop than he did at another theft that had occurred in the cathedral directly across the street.[iii] It was the theft of the “Just Judges” panel and only the most recent of several incidents throughout history involving the “Ghent Altarpiece” by Jan and Hubert van Eyck.

St. Bavo Cathedral, Ghent.[iv]

These “Judges” show up later in history and mystery when they come to play a part in the novel The Fall by Albert Camus published in 1956. A former Parisian lawyer now holds court, so to speak, in a seedy bar in Amsterdam just after World War II. He has assumed the role of a ‘judge penitent’ of the contemporary world.

We are sitting in the café Mexico City, when this stranger intervenes with the bartender on our behalf in ordering the correct gin. It is Jean-Baptiste Clamence and he goes on to fill in some of the history of the bartender and the interior of this place. “Notice, for instance, on the back wall above his head that empty rectangle marking the place where a picture has been taken down. Indeed, there was a picture there, and a particularly interesting one, a real masterpiece.”[v]

“Yet if you read the papers, you would recall the theft in 1934 in the St. Bavon Cathedral of Ghent, of one of the panels of the famous van Eyck altarpiece, ‘The Adoration of the Lamb.’ That panel was called ‘The Just Judges.’ It represented judges on horseback coming to adore the sacred animal. It was replaced by an excellent copy, for the original was never found. Well, here it is. No, I had nothing to do with it.”[vi]

“False judges are held up to the world’s admiration and I alone know the true ones.”[vii]

Anyone with information about the stolen artworks and/or the investigations should contact Anthony Amore, Director of Security at the Gardner Museum, at 617.278.5114 or theft@gardnermuseum.org; or ARCA, the Association for Research into Crimes Against Art, www.artcrime.info; or INTERPOL, General Secretariat, 200 quai Charles de Gaulle, 69006 Lyon, France, E-mail: Contact INTERPOL.

[i] Langton, Jane; Murder at the Gardner; Penguin Books; New York, New York; 1988; p. 81.

[ii] Langton, Jane; Murder at the Gardner; p. 85.

[iii] Charney, Noah; Stealing the Mystic Lamb: The True Story of the World’s Most Coveted Masterpiece; Public Affairs & Perseus Books Group; New York, New York; 2010; p. 145.

[iv] Charney, Noah; Stealing the Mystic Lamb: The True Story of the World’s Most Coveted Masterpiece; (from the section of photographic inserts between pp. 146-147).

[v] Camus, Albert; The Fall; Vintage Books, A Division of Random House; New York, New York; 1956; p. 5.

[vi] Camus, Albert; The Fall; pp. 128-129.

[vii] Camus, Albert; The Fall; p. 130.

In the New Testament both Matthew and Luke relate the story of Jesus being confronted and questioned by the Pharisees, who were pretending to be ‘teachers’ and trying to catch this young man in his own teachings. When questioned by his disciples later, Jesus described the Pharisees like this:

“. . . they are blind guides. And if a blind man leads a blind man, both will fall into a pit.”[i]

It was a powerful image that caught the imagination of many Northern Renaisance artists, especially Pieter Breughel the Elder. Later still, it continued to influence writers such as Charles Baudelaire and William Carlos Williams, who included this subject in his final collection, Pictures from Brueghel, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1963, just two months after that author’s death.

“This horrible but superb painting

the parable of the blind

without a red

in the composition shows a group

of beggars leading

each other diagonally downward

across the canvas

from one side

to stumble finally into a bog

where the picture

and the composition ends back

of which no seeing man

is represented the unshaven

features of the des-

titute with their few

pitiful possessions a basin

to wash in a peasant

cottage is seen and a church spire

the faces are raised

as toward the light

there is no detail extraneous

to the composition one

follows the others stick in

hand triumphant to disaster” [ii]

Paintings by Pieter Breughel and poems by William Carlos Williams have continued to inspire and influence artists and writers today. “Referring to a group of figural drawings he had begun around 1963, Willem de Kooning would say in 1975, ‘I draw while painting, and I don’t know the difference between painting and drawing. The drawings that interest me most are made with eyes closed.’”[iii]

They all looked like scratches, these drawings that de Kooning called ‘blind’ drawings. We first saw them in an exhibition at the Contemporary Arts Center[iv] in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1979. At the time, this exhibition was known as “Recent de Kooning” and featured paintings, drawings, and sculptures completed since 1969.

What we didn’t know at the time, was that de Kooning completed these drawings in a vertical format and later rotated them 90 or 180 degrees in order to further dissorient the viewer. When re-oriented to their original format certain details emerge: these details include several clear references to Breughel’s great painting, “The Parable of the Blind.”

You wouldn’t believe the number of art students who in studying this painting will draw all of the figures straight across the page from left to right, all in a line, and all horizontally. Totally ignoring the descending diagonal from the upper left to the lower right. This of course flattens both the movement and the composition.

One younger artist who noticed this right away was Casey Roberts. Examples of his brush and ink drawings above and below, clearly show that he saw this diagonal movement and took it to a contemporary conclusion. As long time faculty members in various art schools around the country we could all probably be described as the blind leading the blind. An all encompassing metaphor.

[i] “Matthew 15:13-14” The Holy Bible: Revised Standard Version; Thomas Nelson & Sons; New York, Toronto, Edinbugh; 1952; p. 770.

[ii] Williams, William Carlos; Pictures from Brueghel and other poems; New Directions Publishing Corporation; New York, New York; 1967; p. 11.

[iii] Elderfield, John, et al; de Kooning a Retrospective; The Museum of Modern Art; New York, New York; 2011; p. 369.

[iv] Cowart, Jack, and Sanford Sivits Shaman; de Kooning 1969-1978; University of Northern Iowa; Cedar Falls, Iowa; 1978.

“Edward Hopper’s art is highly provocative and often disturbing. His contemplative figures appear to be alienated from society and to occupy a world devoid of interaction and communication. They never smile or frown, and their attitudes and expressions suggest unapproachableness. These introspective figures convey an inner turmoil that can provide questions about relationships, the roles people play in society, and the meaning of life.”[i]

When studying several of Hopper’s sketches for this painting, it becomes clear that he was really searching, working out the space and placement for the lobby and the people inhabiting that space. Five or six different figures were placed in various positions within the composition, including one, a desk clerk, who is hidden in the background behind a lamp in the office. Figures of both men and women are substituted for each other in order to achieve the balance that he desired.

For many years of my teaching career, we would visit the Indianapolis Museum of Art and draw directly from the objects in their collection. There are several works by Edward Hopper housed there, including “American Landscape,” “New York, New Haven and Hartford” and the “Hotel Lobby” from 1943. Especially important in this learning process is to discover the underlying architecture of any work of art, not just the surface illusions. Two such examples are shown above and below this paragraph. Drawings made on the spot in the museum and showing both space and movement and the tonal juxtapositions that occur in the original. They were completed by Darryl W. Hardwick during the summer session of 1976.

The poet Raymond Carver in his collection titled Ultramarine of 1987 took on a similar subject. Not directly written after this painting, the parallels however are so striking that one might do a double take. A quiet, perfectly still scene, with the various characters going about their daily routines. Structured and written to lead us into this particular space. Introspective, with the possibility of great turmoil.

“In the Lobby of the Hotel del Mayo”

“The girl in the lobby reading a leather-bound book.

The man in the lobby using a broom.

The boy in the lobby watering plants.

The desk clerk looking at his nails. The woman in the lobby writing a letter.

The old man in the lobby sleeping in his chair.

The fan in the lobby revolving slowly overhead.

Another hot Sunday afternoon.

Suddenly, the girl lays her finger between the pages of her book.

The man leans on his broom and looks.

The boy stops in his tracks.

The desk clerk raises his eyes and stares.

The woman quits writing.

The old man stirs and wakes up.

What is it?

Someone is running up from the harbor.

Someone who has the sun behind him.

Someone who is barechested.

Waving his arms.

It’s clear something terrible has happened.

The man is running straight for the hotel.

His lips are working themselves into a scream.

Everyone in the lobby will recall their terror.

Everyone will remember this moment for the rest of their lives.”[ii]

[i] Warkel, Harriet G.; Paint to Paper: Edward Hopper’s Hotel Lobby; Indianapolis Museum of Art; Indianapolis, Indiana; 2008; p. 11.

[ii] Carver, Raymond; “In the Lobby of the Hotel del Mayo,” Ultramarine: Poems; Random House; New York, New York; 1987; pp. 75-76.

“His Bathrobe Pockets Stuffed with Notes”

“The early sixteenth-century Belgian painter called, for want of his real name, The Master of the Embroidered Leaf.

Those dead birds on the porch when I opened up the house after being away for three months.

Remember Haydn’s 104 symphonies. Not all of them were great. But there were 104 of them.”[i]

This terrible but beautiful image of a dead bird has always been one of the most haunting paintings in the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC. Just over four inches high it is an important example of works of art that are intimate in size and grand in spirit. Their effect remains with the viewer long after stepping outside of the museum.

Raymond Carver used this technique on several occasions in his work, especially in his collection A New Path to the Waterfall. Small statements, snippets really, are concise and to the point. 16th Century illuminations, dead birds on the front porch, or an incident involving Billy Strayhorn and Duke Ellington all incorporate the painterly criteria of ‘economy of means.’ Compression.

Georgia O’Keeffe’s “Red and Pink Rocks with Teeth” at the Art Institute of Chicago, Jan Vermeer’s “Girl in the Red Hat” at the National Gallery in Washington and Ryder’s “Dead Bird” mentioned above are all small in size but powerful in scale. Why should this be? Perhaps it was the desire of certain figurative painters and Imagist poets for the significant detail: to rivet the universal with the particular. Or, the suggestion made several times by William Carlos Williams throughout his epic poem Patterson to “Say it! No ideas, but in things.”[ii]

Whether it was the search for an American idiom or a single image out of the mass of chaos, Williams would ask of us: “What common language to unravel?”[iii] For both the poet and the painter it would be the process of finding one’s own vision or voice coming out of “…a mass of detail to interrelate on a new ground…pulling the disparate together to clarify and compress.”[iv]

“Because the sun was behind them

their shadows came first and then

the birds themselves.”[v]

To make an image or an object one’s own is to have a signature that comes out of the process of creating that image. Idiosyncratic imagery, like that in Ryder’s painting, has been the trademark of a certain few artists: as in the work of Musa McKim or Leonard Baskin or Susan Rothenberg; Raymond Carver or Kim Fuelling or Michael Ondaatje. These images will speak for themselves, as any real painting or drawing or poem will.

“Through the Boughs”

“Down below the window, on the deck, some ragged-looking birds gather at the feeder. The same birds, I think, that come every day to eat and quarrel. Time was, time was, they cry and strike at each other. It’s nearly time, yes. The sky stays dark all day, the wind is from the west and won’t stop blowing. . . . Give me your hand for a time. Hold on to mine. That’s right, yes. Squeeze hard. Time was we thought we had time on our side. Time was, time was, those ragged birds cry.”[vi]

“Application for a Driving License”

“Two birds loved

in a flurry of red feathers

like a burst cottonball,

continuing while I drove over them.

I am a good driver, nothing shocks me.”[vii]

[i] Carver, Raymond; “His Bathrobe Pockets Stuffed with Notes;” A New Path to the Waterfall; The Atlantic Monthly Press; New York, New York; 1989; pp. 64-66.

[ii] Williams, William Carlos; Patterson; New Directions Publishing Corporation; New York, New York; 1992; p. 7.

[iii] Williams, William Carlos; Patterson; p. 9.

[iv] Williams, William Carlos; Patterson; p. 19.

[v] McKim, Musa; Alone With the Moon, Selected Writings; The Figures; Great Barrington, Massachusetts; 1994; p. 137.

[vi] Carver, Raymond; “Through the Boughs;” A New Path to the Waterfall; p. 120.

[vii] Ondaatje, Michael; “Application for a Driving License;” The Cinnamon Peeler; Vintage International; New York, New York; 1997; p. 14.

Between 1902 and 1914 the poet Rainer Maria Rilke lived in Paris to work on a monograph and to act for a short time as the secretary for the sculptor August Rodin. It was Rodin who introduced him to other Parisian artists of the time, including Paul Cezanne. Influenced by the physicality of many of the paintings and sculptures he saw, Rilke developed a new style, which he called the “object poem.” This form of writing sought to capture the plastic presence of a physical object and resulted in imaginative interpretations of certain works of art.

Rilke began writing the “Duino Elegies” in 1912 while a guest of Princess Marie von Thurn und Taxis at the Duino Castle near Trieste. For the next ten years however, the “Elegies” remained incomplete whilst Rilke fell frequently in and out of a depression partially caused by the events of World War I.

In 1915, while he was living in Munich and finding it difficult to secure suitable housing, Rilke asked Hertha Koenig if he might live for a while in her house while she and her family were in the country. His request was granted, and he lived there from June until October 1915. Sometime in 1914 Frau Koenig had purchased Picasso’s painting “The Family of Saltimbanques” and this is where Rilke was privileged to have lived with this painting for five months.

Later, in the summer of 1921 Rilke took up residence at the Château de Muzot, as the guest of another patron. Within the space of a few days in February 1922, he completed the Duino cycle, begun years earlier. The final section to be completed was the Fifth Elegy, which was dedicated to Frau Hertha von Koenig and based on this rose period masterpiece: “The Family of Saltimbanques.”

“But tell me, who are they, these acrobats, even a little

more fleeting than we ourselves,–so urgently, ever since childhood

wrung by an (oh, for the sake of whom?)

never-contented will? That keeps on wringing them,

bending them, slinging them, swinging them,

throwing them and catching them back; as though from an oily

smoother air, they come down on the threadbare

carpet, thinned by their everlasting

upspringing, this carpet forlornly

lost in the cosmos.

Laid on there like a plaster, as though the suburban

sky had injured the earth.”[i]

“There, the withered wrinkled lifter,

old now and only drumming,

shriveled up in his mighty skin as though it had once contained

two men, and one were already

lying in the churchyard, and he had outlasted the other,

deaf and sometimes a little strange.”[ii]

Who are they? They have become one and the same color as the sand and sawdust beneath their feet. Almost ghosts. It is a huge painting at the National Gallery with figures almost life size who know how to keep secrets. Even the painting itself has a secret: look for the water jug just behind the woman in the lower right, and the pointed stance of the young acrobat to her left, below that and just beneath the surface is a ghost of a leg, a pentimento of another earlier figure, now painted out of the picture. This lost figure, as well as the surviving ones are all ghosts now, inhabiting the rose desert of Rilke’s poem, but not always adding up to zero.

“And the yonger, the man, like the son of a neck

and a nun: so taughtly and smartly filled

with muscle and simpleness.”[iii]

“And then, in this wearisome nowhere, all of a sudden,

the ineffable spot where the pure too-little

incomprehensibly changes,–springs round

into that empty too-much?

Where the many-digited sum

solves into zero?”[iv]

[i] Rilke, Rainer Maria; The Duino Elegies, translated by J. B. Leishman and Stephen Spender; W. W. Norton & Company; New York, New York; 1963; p. 47.

[ii] Rilke, Rainer Maria; The Duino Elegies; p. 49.

[iii] Rilke, Rainer Maria; The Duino Elegies; p. 49.

[iv] Rilke, Rainer Maria; The Duino Elegies; p. 53.

There is a story regarding the poet William Carlos Williams and the painter Marsden Hartley that recounts an early shared experience. Dr. Williams was working at the time at the Post Graduate Clinic in New York and after his shift had made arrangements to visit Hartley’s studio. Hartley however, was either late or had totally forgotten the appointment and Williams sat for a few minutes on the stoop in front of the building. It was getting dark, streetlights were coming on and firetrucks were racing past. Williams got out a piece of paper and wrote down, or sketched out, the entire scene. It became his poem “The Great Figure” and was published as part of his collection Sour Grapes in 1921.

A few years later Charles Demuth began a series of eight abstract “poster portraits” as tributes to other modern American artists, amongst them were Georgia O’Keeffe, John Marin and Arthur Dove. Although these were not literal likenesses, Demuth created these portraits using imagery that related to each sitter. In William Carlos Williams’ case urban sights and sounds, cubist directional lines and a number on the side of a passing firetruck are all incorporated into this one particular painting.

“The Great Figure”

“Among the rain

and lights

I saw the figure 5

in gold

on a red

firetruck

moving

tense

unheeded

to gong clangs

siren howls

and wheels rumbling

through the dark city”[i]

Williams’ poem became a classic example of the new writing in America known as Imagism. Charles Demuth’s painting was purchased by Alfred Stieglitz and later donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. And later still, during the Pop Art period, Robert Indiana appropriated this image for a series of his own paintings and silkscreen prints titled the “American Dream.” Examples of these works are now in the collection of the Indianapolis Museum of Art.

[i] Williams, William Carlos; The Collected Poems: Volume I; New Directions Publishing Corporation; New York, New York; 1986; p. 174.

At the Salon of 1907 in Paris, the critic Louis Vauxcelles described the “Blue Nude” as: “A nude woman, ugly, spread out on opaque blue grass under some palm trees.”[i]

In 1913 in New York and Chicago the Armory Show was a catalyst for derision of both European and modern art by the general American population. It was of course the first exposure of works by Cezanne, Picasso, Matisse, and even Ingres to the American public. This exhibition also included selected contemporary American artists, including several who were associated with Alfred Stieglitz and his gallery.

Henri Matisse’s early painting, “Blue Nude, a Souvenir of Biskra” from 1907 was one of the pieces to cause a public stir. At the close of the exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1913, the students rioted and burned both the painting and Matisse in effigy on the steps of the museum.

The painting had been purchased by Leo Stein in Paris at the 1907 Salon. Later it was purchased by the American collector John Quinn, whose estate in turn sold it to Etta and Claribel Cone of Baltimore, where it remains in the collection of the Baltimore Museum of Art.

The Blue Nude was also featured in an exhibition at Stieglitz’s gallery in 1921, where it was seen by the American poet William Carlos Williams. His prose poem, inspired by this painting, may be one of the first positive pieces of writing regarding the “Blue Nude.”

“A Matisse in New York”

“On the french grass, in that room on Fifth Ave., lay that woman who had never seen my own poor land.”

“So he painted her. The sun had entered his head in the color of sprays of flaming palm leaves. They had been walking for an hour or so after leaving the train. They were hot. She had chosen the place to rest and he had painted her resting, with interest in the place she had chosen.”

“It was the first of summer. Bare as was his mind of interest in anything save the fullness of his knowledge, into which her simple body entered as into the eye of the sun himself, so he painted her.”

“No man in my country has seen a woman naked and painted her as if he knew anything except that she was naked. No woman in my country is naked except at night.”

“In the french sun, on the french grass in a room on Fifth Ave., a french girl lies and smiles at the sun without seeing us.”[ii]

More recently, in 1993 the English writer A. S. Byatt has taken a similar approach to this subject in The Matisse Stories, a series of short stories each inspired by one of Matisse’s paintings. This time, it is the “Large Reclining Nude” also known as the “Pink Nude” purchased in 1936 directly from the artist by Etta Cone and donated to the Baltimore Museum of Art through the Cone Sisters’ bequest in 1950.

Dr. Claribel Cone’s will stated that the Baltimore Museum of Art should receive the bequest of their collection provided that “…the spirit of appreciation for modern art in Baltimore became improved.”[iii]

“She had walked in one day because she had seen the Rosy Nude through the plate glass. That was odd, she thought, to have that lavish and complex creature stretched voluptuously above the coat rack, where one might have expected the stare, silver and supercilious or jetty and frenzied, of the model girl. They were all girls now, not women. The rosy nude was pure flat colour, but suggested mass. She had huge haunches and a monumental knee, lazily propped high. She had round breasts, contemplations of the circle, reflections on flesh and its fall. . . . She had asked cautiously for a cut and blow-dry.”[iv]

In conversations with his friends and fellow artists over the years, especially with the poet Louis Aragon, Matisse often stated that: “The importance of an artist is to be measured by the number of new signs he has introduced into the plastic language…”[v]

[i] Flam, Jack; Matisse in the Cone Collection: The Poetics of Vision; The Baltimore Museum of Art; Baltimore, Maryland; 2001; pp. 41-42.

[ii] Tashjian, Dickran; William Carlos Williams and the American Scene 1920-1940; Whitney Museum of American; New York, New York; 1978; 29-31.

[iii] Flam; Matisse in the Cone Collection; p. 7.

[iv] Byatt, A. S.; The Matisse Stories; Vintage International; New York, New York; 1996; p. 3.

[v] Flam, Jack; Matisse on Art; University of California Press; Berkeley, Los Angeles, London; 1995; p. 150.

“Someone, I tell you, in another time,

will remember us.”[i]

Ekphrasis or ecphrasis, from the Greek: a description of a work of art, either real or imaginary, produced as a rhetorical exercise; often used in the adjectival form, ekphrastic, a graphic, often dramatic, description of a visual work of art.

From ancient times to the 20th century there has been an interdisciplinary dance played out between poets and painters. The idea of writing a poem or a play that was descriptive of, or inspired by a work of visual art was in fact invented by the Greeks. Homer’s description of the Shield of Achilles in the 18th Book of The Illiad being one of the first examples.

“Then first he form’d the immense and solid shield;

Rich various artifice emblazed the field;

Its utmost verge a threefold circle bound;

A silver chain suspends the massy round;

Five ample plates the broad expanse compose,

And godlike labours on the surface rose.

There shone the image of the master-mind:

There earth, there heaven, there ocean he design’d;

The unwearied sun, the moon completely round;

The starry lights that heaven’s high convex crown’d;

The Pleiads, Hyads, with the northern team;

And great Orion’s more refulgent beam;

To which, around the axle of the sky,

The Bear, revolving, points his golden eye,

Still shines exalted on the ethereal plain,

Nor bathes his blazing forehead in the main.”[ii]

This was of course, a literary fiction based totally on a plastic fiction, made real through the art of storytelling. The Romantic poet John Keats harks back to classic examples with his “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” Published anonymously in the January 1820, Number 15 issue of the magazine “Annals of the Fine Arts” it is an elegaic description on this single object. Early speculation centered around the fact that Keats had based his poem on a specific vase, either “The Sosibios Vase” at the Louvre in Paris or later on “The Townley Urn” at the British Museum in London. Nowadays it is considered that his work is more of a synthesis of several objects.

“Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness,

Thou foster-child of silence and slow time,

Sylvan historian, who canst thus express

A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme:

What leaf-fring’d legend haunts about thy shape

Of deities or mortals, or of both,

In Tempe or the dales of Arcady?

What men or gods are these? What maidens loth?

What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape?

What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?”

“O Attic shape! Fair attitude! with brede

Of marble men and maidens overwrought,

With forest branches and the trodden weed;

Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought

As doth eternity: Cold Pastoral!

When old age shall this generation waste,

Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say’st,

Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”[iii]

Keats ends his poem with an observation that has become an everlasting philosophical debate: “Beauty is truth, truth beauty.” From artists’ arguments in cafes and bars to doctoral dissertation defenses, it has become an ongoing discussion. Whether writing directly from a work of art as the primary source, as Keats has done, or inventing an image and then writing about it, this form of inspiration flows directly from the visual artist to the writer. In some more recent cases the artist seizes upon an image written by a poet and then makes a drawing or painting.

Near the end of his life, the 20th century abstract painter Philip Guston chose an entire new direction for his work, seeming to reject everything he had created before. He got himself hated by many former friends, but not everyone. Younger poets and painters recognized this new figuration, not as a retreat back into a mimetic mode, but as a venture into a new plastic and literary arena. His late drawings and paintings are a rare example of real dialogue between one painter and several contemporary poets. These poets included: Clark Coolidge, Bill Bergson, Musa McKim, Anne Waldman, William Corbett, Frank O’Hara and Stanley Kunitz.

A generation later, young painters who had studied exclusively with abstract artists in school struggled to find their own voices and visions. It seemed like a dead end to continue without a subject, or subject matter. At first they were accused of producing ‘bad’ painting. With a few more artists testing these waters they became known as ‘New Image’ painters and even ‘neo-expressionists.’ Amongst these artists were: Susan Rothenberg, Robert Moskowitz, Elizabeth Murray and Neil Jenney. All were working, in no small part, thanks to the doors that Philip Guston had opened.

“Henceforth a painting was a legible record of all the decisions, whether tentative or assured, that went into its conception and realization. The issue was not one of speed . . . but rather one of the immediacy and responsiveness of process, the simultaneity of thinking and making.”

Philip Guston [iv]

[i] Sappho; “No Oblivion,” The Complete Poems of Sappho (translated by Willis Barnstone); Shambala Publications; Boston & London; 2011; [147].

[ii] Translated by Alexander Pope. This poem is in the public domain.

[iii] Keats, John; John Keats: The Major Works; Oxford University Press; Oxford & New York; 1990 & 2001; pp. 288-289.

[iv] Storr, Robert; Philip Guston; Abbeville Press; New York, New York; 1986; p. 25.