This is going to be messy! In ancient times in Brittany, there were magicians and wise men and martyrs roaming the countryside, often secluding themselves in the nearby forests. In equal numbers of cases, there were heroic as well as villainous knights, many soon to become martyrs. So many of them were killed in battles or through torture, including beheadings over the years, that the early church had to invent a specific word for this: “cephalophores.”

“Saint Trémeur”

XVIIe Century

Bois polychrome

Chapelle Saint-Trémeur,

Bury, France

At the beginning of each Summer Session in 1995, 1997, 2000, and 2007, while teaching at the Pont-Aven School of Contemporary Art in Brittany, France, there would always be a school-wide orientation followed by field trips to the local churches and museums. All local institutions with regional collections filled with histories and legends.

During these trips, many of the local stories were passed down to us by word of mouth. One important story related how a certain figure had suffered a beheading in battle, whereupon he picked up his own head and carried it out into the Brocéliande Forest where Merlin the Magician supposedly lived. Merlin returned this young man’s head to its correct position so that revenge could be accomplished. It parallels so many other stories in the history of ‘cephalophores!’

“Saint Trémeur”

XVIe Century

Pierre de kersanton

Le Musée Departmental Breton,

Quimper, France

In one of the local bookstores I discovered a small collection of stories titled Celtic Legends of Brittany containing many references to the local people and history. One especially was the story of Trémeur who was beheaded by his step-father Conmore. Conmore was totally against the Catholic Church and its proselytizing in the area. His wife Trephine had become interested in this new religion and so she was killed by her own husband.

“Years passed, when one day as Conmore was walking in the woods he came to the very spot where he had slain Trephine. There he found children playing, one of whom was called by his companions Tremeur. The name attracted his attention. He looked at the child and asked him his age.”

“‘I shall soon be nine’, he replied.”

“Conmore thought for a moment. He had the intuition, soon the certainty, that this child before him was the son of himself and Trephine. Quick as a flash he drew his sword and struck the child’s head off, as he had struck off the head of his mother, and then hastened away.”

“The little martyr, says the legend, when the tyrant was gone, took his head in his hands and carried it to the side of his mother’s tomb where she was sleeping. In the cemetery of St. Trephine is a chapel, of modern construction, covering the tomb of Tremeur, which is not far from that of his mother. Inside the church, five round stones emerge. The people declare they are the stones with which Tremeur was playing when he was struck down by his father.”1

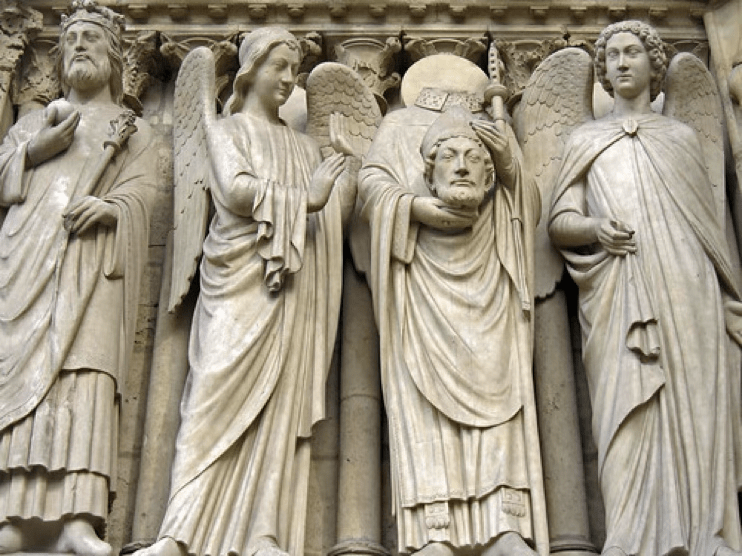

The greatest story along these lines of course is that of St. Denis, the first bishop of Paris. There are several sculptural representations of St. Denis included in the collections of both the Musée Cluny and the Louvre as well on the walls of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris.

From the outside walls of Notre Dame Cathedral

(after the major renovation of the 19th Century by Viollet-le-Duc)

Paris, France

During an anti-Christian period in Paris, St. Denis was evangelizing in the area when he was beheaded by the Romans on what is now Montmartre. It is said that he picked up his own head and continued his sermon as he walked across the city to the site he had chosen for his own grave. On this site he was buried in a small chapel.

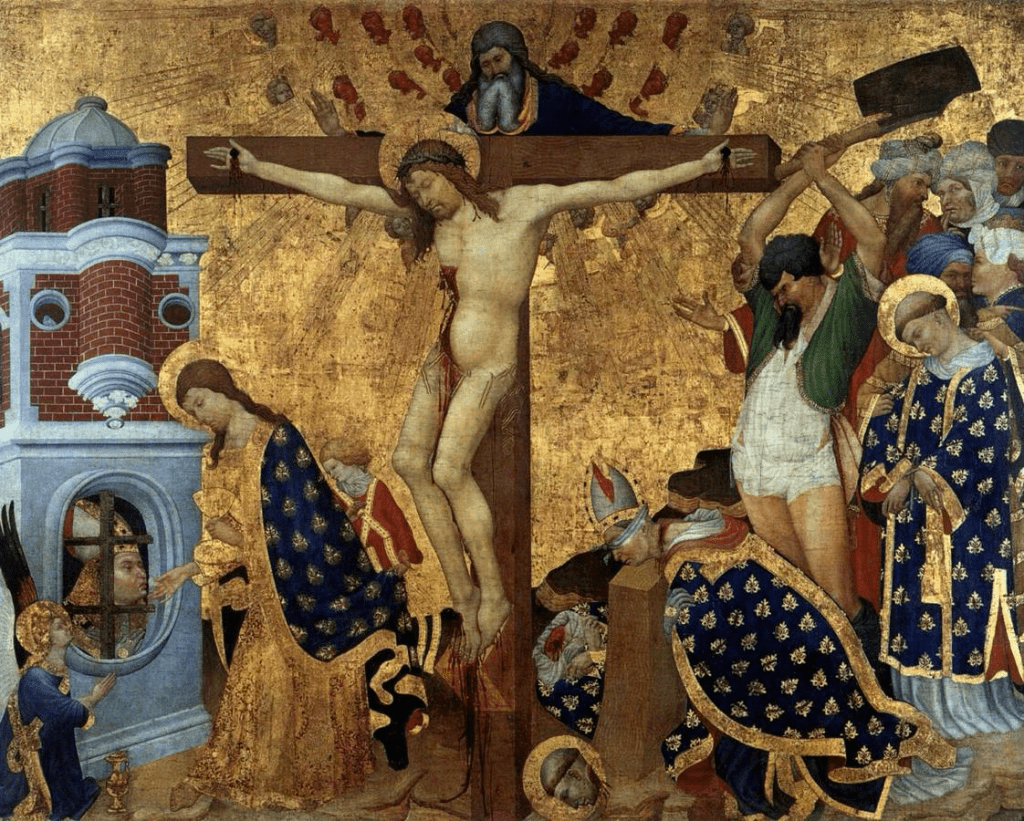

“Calvary and the Martyrdom of St. Denis”

1415-1416

Tempera and gold leaf on canvas and panel

162cm x 211cm

Musée Louvre, Paris

Later this chapel was dedicated as an Abbey and the architect Suger was designated by the Pope to revitalize it. In the process it was dedicated as the Abbey of St. Denis in the town of the same name. As Abbot Suger designed the building and rebuilt the altar and the upper choir from 1135 to 1144, he clarified his theories on both light and structure, combining the old and the new in harmony, defining what would become Gothic Architecture. It became the resting place for many of the Kings of France and is now known as the Basilique Cathédrale de Saint-Denis.

Here, taken from the writings of Suger, is part of his vision for synthesizing the reconstruction of the chapel that St. Denis chose for his burial.

“The admirable power of one unique and supreme reason equalizes by proper composition the disparity between things human and Divine; and what seems mutually to conflict by inferiority of origin and contrariety of nature is conjoined by the single, delightful concordance of one superior, well-tempered harmony.”2

Side Aisles, Transept’s, Upper Choir and Facade

1135-1144

St. Denis, France

In tribute to Saint Denis, here is what Abbot Suger had written into the Panel on the Altar Front in the Upper Choir at the Chapel of St. Denis:

“Great Denis, open the door of Paradise

And protect Suger through thy pious guardianship.”

“That which is signified pleases more than that which signifies.”3

1 Aubert, O.-L.; Celtics Legends of Brittany; COOP BREIZH; Spézet, Brittay, France; 1993; pp. 86-87.

2 Panofsky, Erwin (Translator and Editor); Abbot Suger: On the Abbey Church of St.-Denis and It’s Art Treasures; Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey; 1946; p. 83.

3 Panofsky, Erwin (Translator and Editor); Abbot Suger: On the Abbey Church of St.-Denis and It’s Art Treasures; Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey; 1946; p. 55.