“The sanctuary was lost for centuries because this ridge is in the most inaccessible corner of the most inaccessible section of the central Andes. No part of the highlands of Peru is better defended by natural bulwarks—a stupendous canyon whose rock is granite, and whose precipices are frequently 1,000 feet sheer, presenting difficulties which daunt the most ambitious modern mountain climbers. Yet, here, in a remote part of the canyon on this narrow ridge flanked by tremendous precipices, a highly civilized people, artistic, inventive, well organized, and capable of sustained endeavor, at some time in the distant past built themselves a sanctuary for the worship of the sun.”1

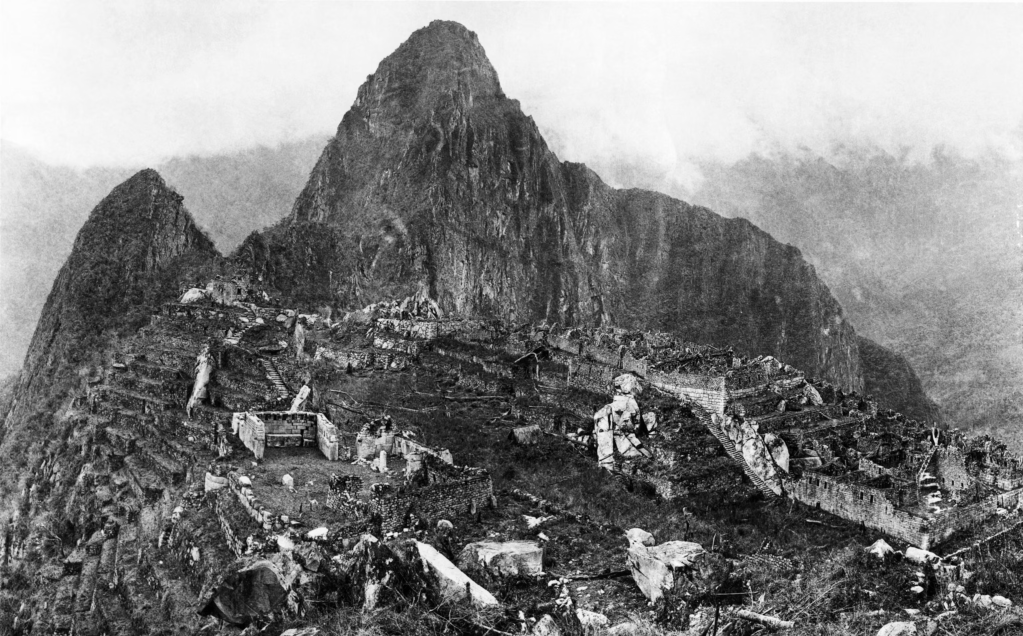

“The story of Machu Picchu: the Peruvian expeditions of the

National Geographic Society and Yale University”

B&W photograph

National Geographic Magazine, v. 27, Feb. 1915: p. 172.

Here are the observations and notations of Hiram Bingham upon his re-discovery of Machu Picchu through a series of expeditions, the first one sponsored by Yale University and the following ones by the National Geographic Society. Although the native Peruvian people had known of this place for years, many had already migrated into the area in and around Cusco. Bingham was able to hire a few guides and assistants for his explorations on each trip, and he kept very thorough journals and records, including photographs.

On our recent tour in late October 2025 we flew from Lima over the Andes and then down into the Sacred Valley and the city of Cusco. From there, a series of train rides and buses delivered us to the great city of Machu Picchu.

It truly felt like ancient footprints were everywhere, especially since many of the stairs were carved out of the living rock. Unfortunately hardly any two steps were of the same proportion or height. Using our hiking sticks and keeping our eyes on the path, we warned each other of rocks in the pathway and uneven steps, which often occurred when least expected.

It was only after climbing several sets of steep steps, keeping our eyes on both the walls and steps, that the views opened up on a larger plain and the surrounding structures.

There are many examples of literature inspired directly from this work of art, the great architectural site of Machu Picchu. The first of course is from Hiram Bingham’s direct observations following his re-discovery of this site in 1911-1912. Many others are more modern. Because of the three different languages spoken locally, Quechua, Aymara and Spanish, I have left the various spellings intact, so the mistaken names of some locations and the name Machu or Macchu are quoted as in the originals. These are not misspellings.

“Suddenly I found myself confronted with the walls of ruined houses built of the finest quality of Inca stone work. It was hard to see them for they were covered with trees and moss, the growth of centuries, but in the dense shadow, hiding in bamboo thickets and tangled vines, appeared here and there walls of white granite ashlars carefully cut and exquisitely fitted together. We scrambled along through the dense undergrowth, climbing over terrace walls and in bamboo thickets, where our guide found it easier than I did. Suddenly, without any warning, under a huge overhanging ledge the boy showed me a cave beautifully lined with the finest cut stone. It had evidently been a royal mausoleum. On top of this particular ledge was a semicircular building whose outer wall, gently sloping and slightly curved, bore a striking resemblance to the famous Temple of the Sun in Cuzco. This might also be a temple of the sun. It followed the natural curvature of the rock and was keyed to it by one of the finest examples of masonry I had ever seen. Further it was tied into another beautiful wall, made of very carefully matched ashlars of pure white granite, especially selected for its fine grain. Clearly, it was the work of a master artist. . . .”2

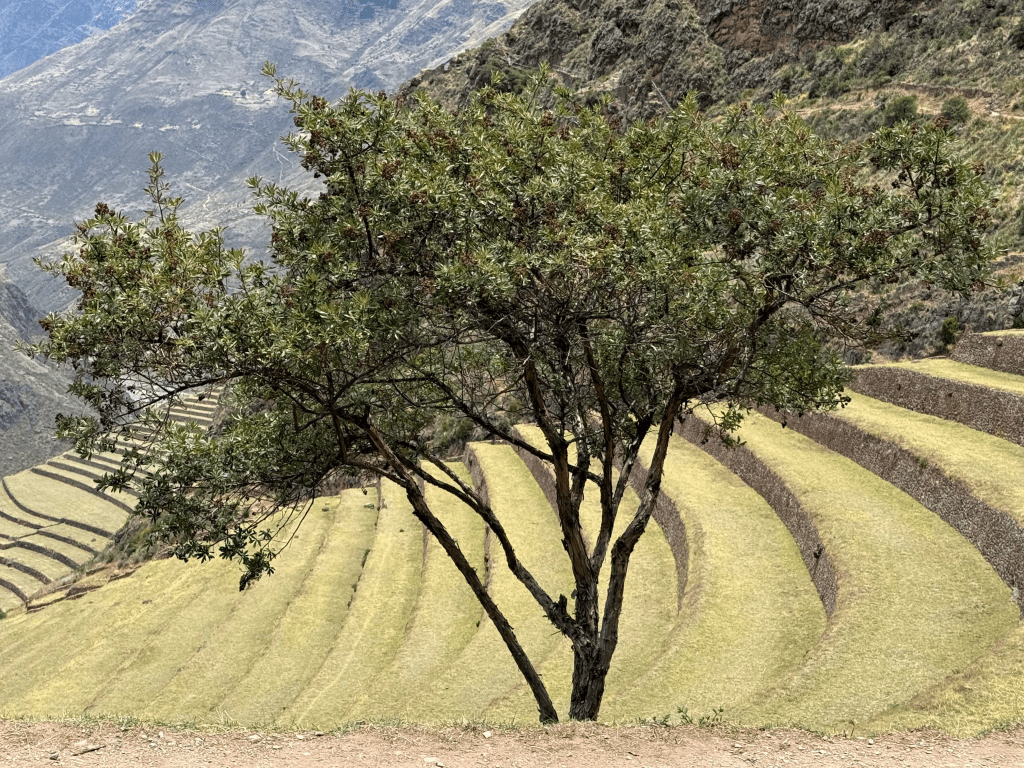

“The Inca Wall at Ollantaytambo,

near Machu Picchu, Peru”

2025

Digital photograph

“. . . . The interior surface of the wall was broken by niches and square stone-pegs. The exterior surface was perfectly simple and unadorned. The lower courses, of particularly large ashlars, gave it a look of solidity. The upper courses, diminishing in size towards the top, lent grace and delicacy to the structure. The flowing lines, the symmetrical arrangement of the ashlars, and the gradual graduation of the courses, combined to produce a wonderful effect, softer and more pleasing than that of the marble temples of the Old World. Owing to the absence of mortar, there were no ugly spaces between the rocks. They might have grown together. On account of the beauty of the white granite this structure surpassed in attractiveness the best Inca walls in Cuzco, which had caused visitors to marvel for four centuries. It seemed like an unbelievable dream. Dimly, I began to realize that this wall and its adjoining semicircular temple over the cave were as fine as the finest stonework in the world.”3

Surprisingly, the second example is from a novel which is set in Machu Picchu by Mark Adams. In this novel, we have an editor/explorer and his colleagues in search of an adventure and comically retracing the journey of Hiram Bingham. As a footnote to all of this, there is the ironic possibility that a modern day cinema legend may have actually been based on Hiram Bingham.

“There’s an old kitchen maxim that squid should either be cooked for two minutes or two hours. A similar rule could be applied to Machu Picchu. With a good guide—there are dozens of them lingering by the front entrance—a visitor who’s short on time can see the highlights of Machu Picchu in two hours. A visit of two days, though, allows enough time to take in the site’s full majesty. Our plan was to devote one day to retracing Bingham’s 1911 footsteps, and a second to seeing some parts of the site that most people never get to.”4

“As a magazine editor, I knew the revised version of Bingham’s tale had the makings of a great story: hero adventurer exposed as villainous fraud. To get a clearer idea of what had really happened on that mountaintop in 1911, I took a day off and rode the train up to Yale. I spent hours in the library, leafing through Bingham’s leather-coated notebook in which Bingham had penciled his first impressions of Machu Picchu, any thoughts of the controversies fell away. Far more interesting was the story of how he had gotten to Machu Picchu in the first place. I’d heard that Bingham had inspired the character Indiana Jones, a connection that was mentioned—without much evidence—in almost every news story about the explorer in the last twenty years. Sitting in the neo-Gothic splendor of Yale’s Rare Books and Manuscripts Room, the Indy-Bingham connection made sense for the first time. Bingham’s search had been a geographic detective story, one that began as a hunt for the Lost City of the Incas but grew into an all-consuming attempt to solve the mystery of why such a spectacular granite city had been built in such a spellbinding location: high on a secluded mountain ridge, in the misty subtropical zone where the Andes meet the Amazon. Fifty years after Bingham’s death, the case had been reopened. And the clues were still out there to be examined by anyone with strong legs and a large block of vacation time.”5

“Trees and Terraces Surrounding the Area

on the way up to Machu Picchu”

2025

Digital photograph

The final literary example is from Pablo Neruda, an epic lyrical poem imagined and inspired by Macchu Picchu, the wonder of its construction, and the labor and the hardships that it must have cost.

VI

“And then the stairs of the earth I ascended

through the savage tangle of the lost jungles

to you, Macchu Picchu.

High city of stepped stones,

sanctuary at long last of what the earth

never hid away in its nightclothes.

In you, like two parallel lines,

the cradle of lightning and the cradle of man

were rocked by a wind of thorns.

Mother of stone, sperm of condors.

High stone road of the human dawn.

Lost shovel in the primordial sand.

This was the home, this was the place:

here the plump grains of maize climbed

and like red hail came back down again.

Here the vicuña gave the gold thread

to clothe love, tombs, mothers,

the king, prayers, warriors.

Here the feet of men rested at night

next to the feet of the eagle, in the high bloody

lairs, and at first light

they stepped with thunderous feet on the tense mist,

and then tucked the earth and the stones

until they would have known them even at night or in death.

I stare at the clothes and hands,

the carvings of water in a sonorous hollow,

the wall rubbed smooth by the touch of a face

that with my eyes gazed at the earthly lights,

that with my hands oiled the vanished

planks: because everything, clothes, skin, dishes,

words, wine, breads,

went away, fell to the earth.

And the air came with its fingers

of orange blossom over all of the sleepers:

a thousand years of air, months, weeks of air,

of a blue wind, of an iron mountain ridge,

that was like a soft hurricane of footfalls

polishing the solitary site of stone.”6

“The Secret Chamber Beneath

the Temple of the Sun at Machu Picchu”

2025

Digital photograph

Anne McKenzie Nickolson and Tom Lundberg had been classmates in the Graduate Textiles Program at Indiana University for a time in the mid-1970’s. After Tom moved to Ft. Collins, Colorado to teach at Colorado State University he met Marilyn Murphy who was a textile writer/editor and President of the Andean Textile Arts organization. Of course all three of them were interested in the 25th Annual Andean Textile Arts tour to Peru in October 2025, especially focussing on the communities in and around Cuzco and the Sacred Valley. Our tour guides were the brothers Raul and Wilson Jaimes who were so very knowledgeable on all of Peruvian history and culture.

I was equally excited about this tour, especially as it related to the communities in the Sacred Valley and the chance to follow in some of Hiram Bingham’s footsteps and visit Machu Picchu for two days. I immediately bought new ink pens and sketchbooks for the trip.

The drawing portfolio included below is in the exact order in which they were done, on site, “en plein air” in each case. They begin with the first and second days at Machu Picchu, and include my last drawing there on the high path leading to the Inca Bridge. The following ones are all at the Temple of the Sun in Cusco containing the original Incan walls with a museum built over top. The last two are on the lower plain with the Wall of the Giants, constructed with many 200 to 300 ton stones, followed by one last Grain Storage Shed, one of my fondest memories.

“Terraces and Stairways”

27 October 2025

Pen & Ink on Paper

8 1/2” x 6”

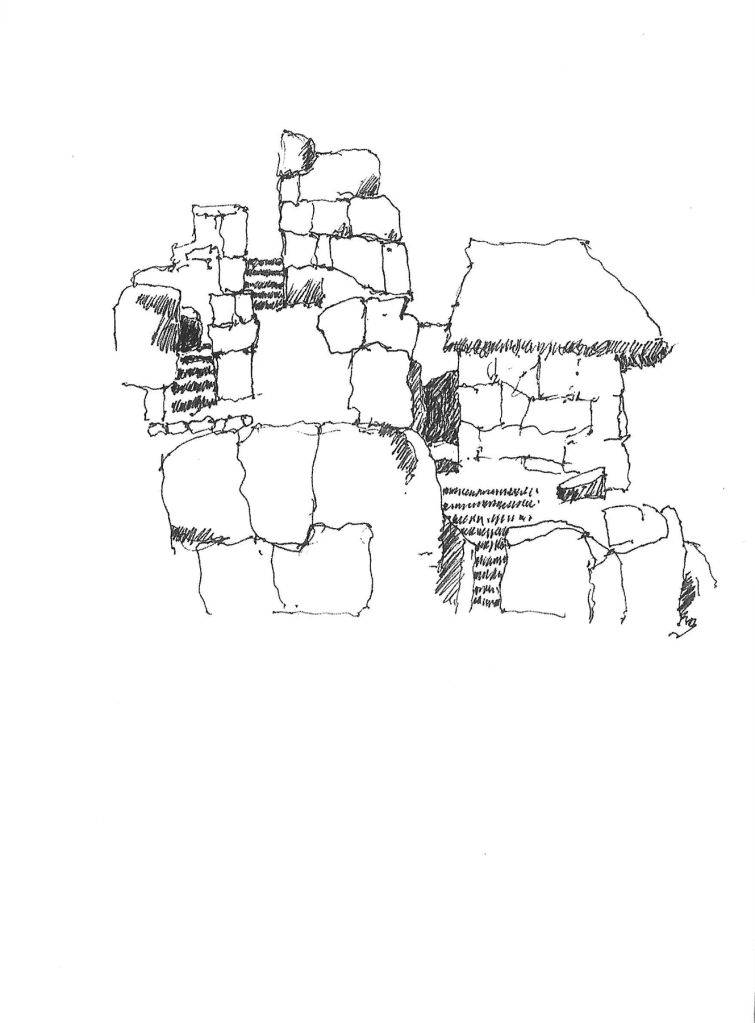

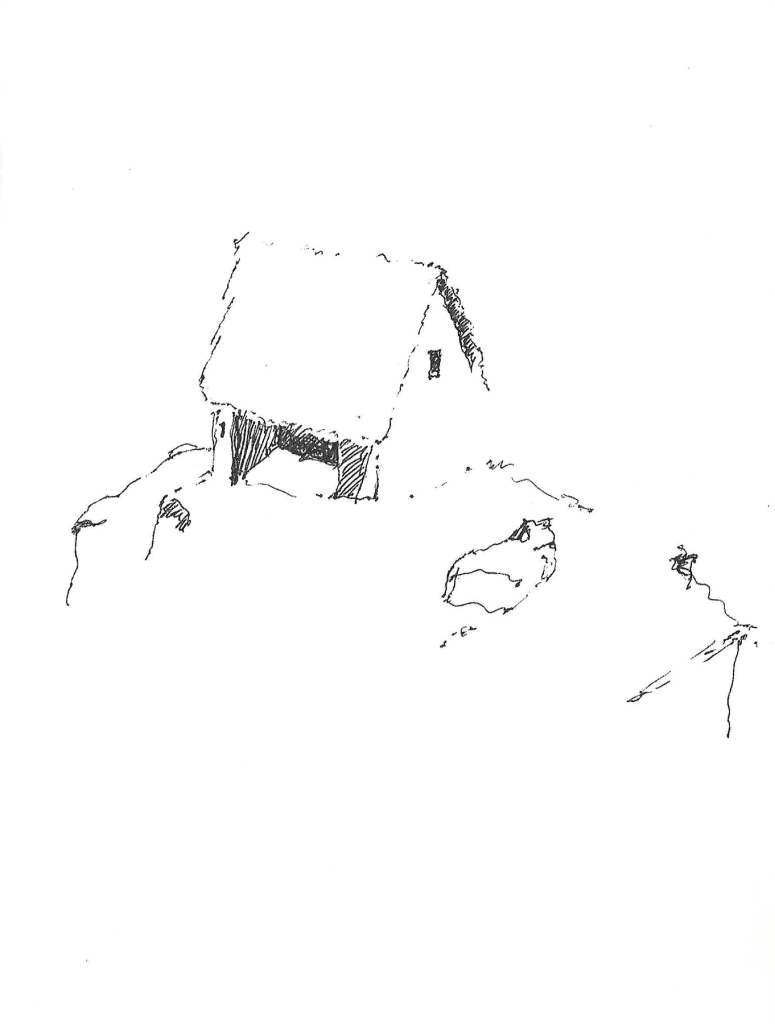

“The First Grain Storage Shed”

27 October 2025

Pen & Ink on Paper

8 1/2” x 6”

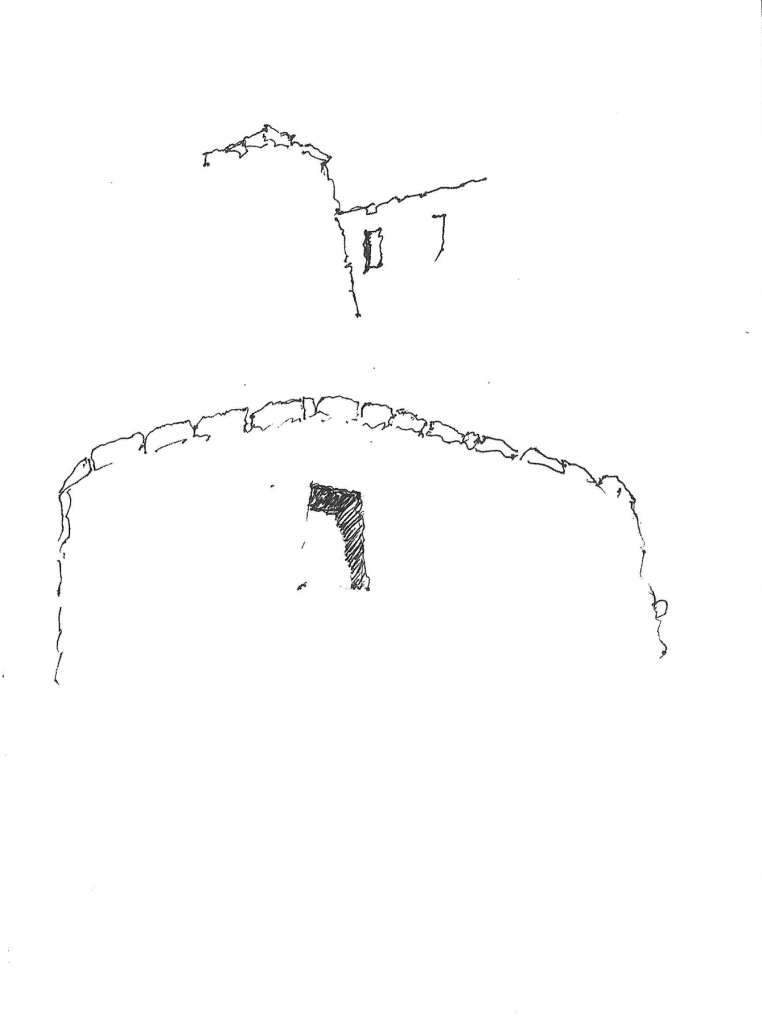

“The Tower of the Sun at Machu

Picchu w/Small Tower Above”

27 October 2025

Pen & Ink on Paper

8 1/2” x 6”

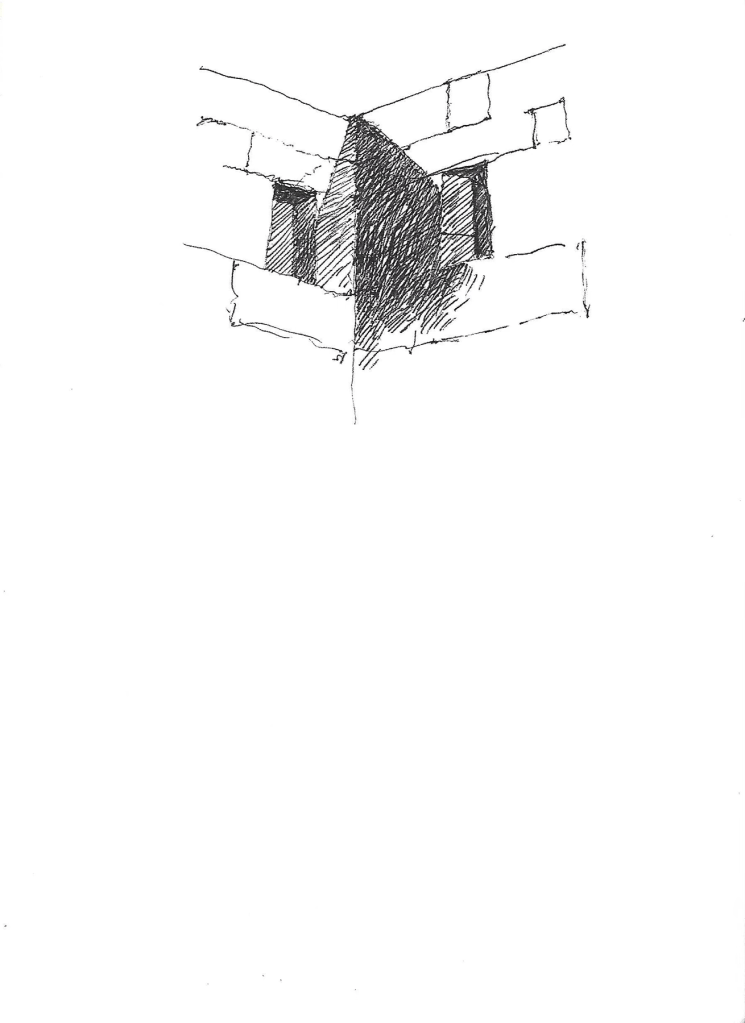

“The Stair-stepped Window”

28 October 2025

Pen & Ink on Paper

8 1/2” x 6”

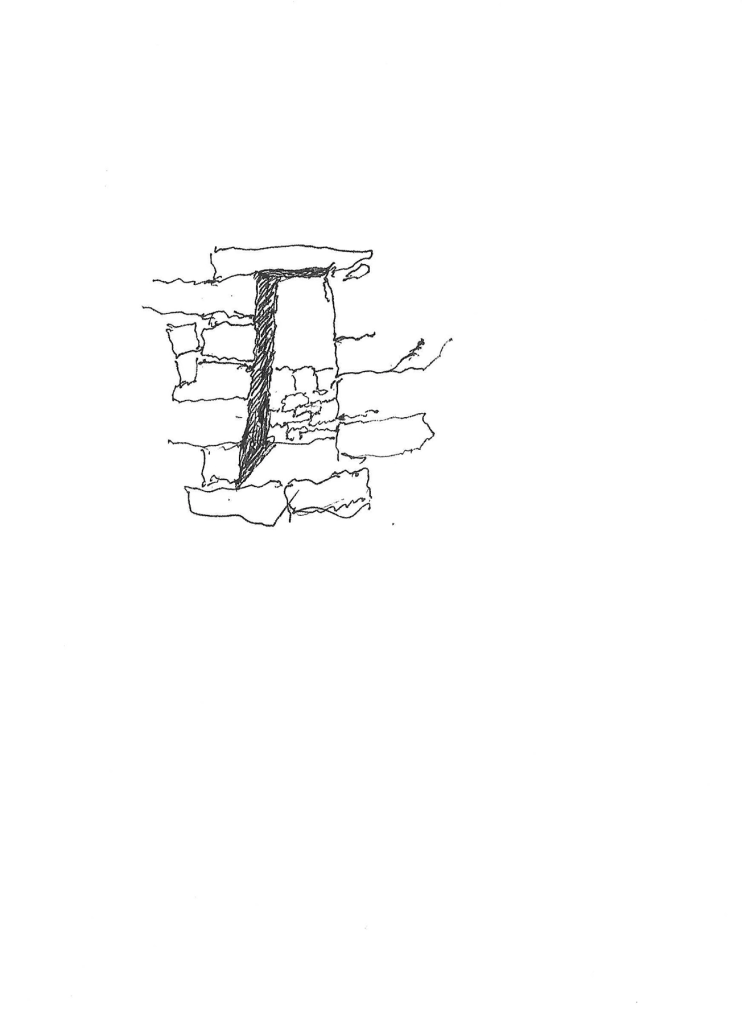

“A Window Detail”

28 October 2025

Pen & Ink on Paper

8 1/2” x 6”

“The Second Grain Storage Shed”

28 October 2025

Pen & Ink on Paper

8 1/2” x 6”

“The Artist Drawing Along the High Path

Towards the Inca Bridge”

28 October 2025

Digital Photograph

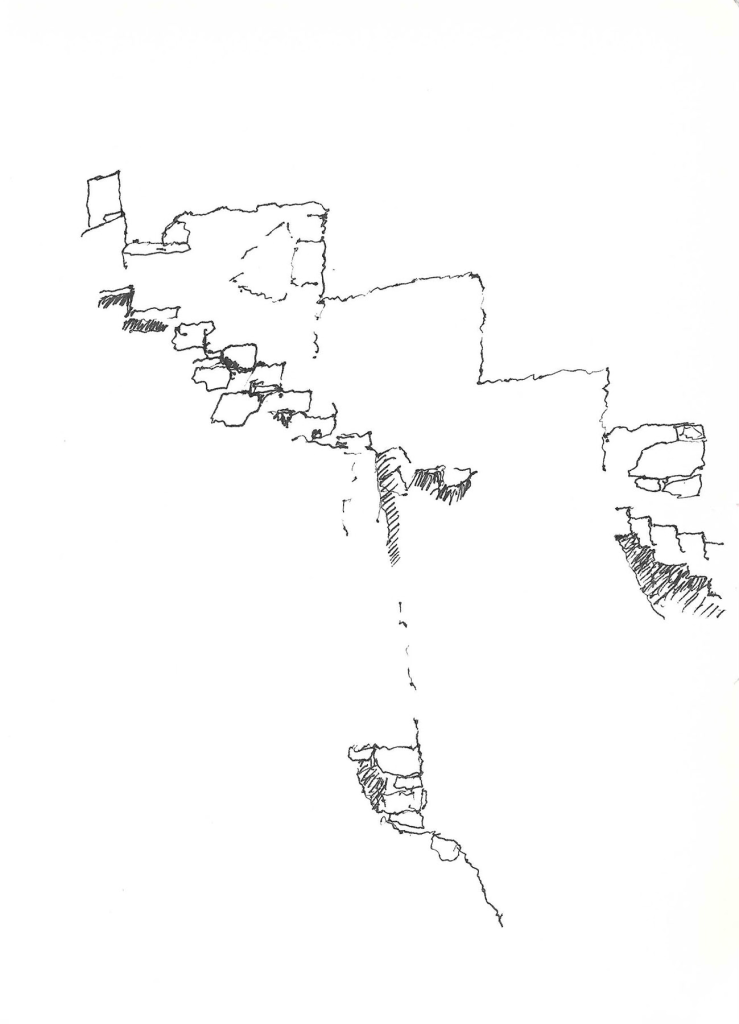

“The High Path Towards the Inca Bridge”

28 October 2025

Pen & Ink on Paper

8 1/2” x 6”

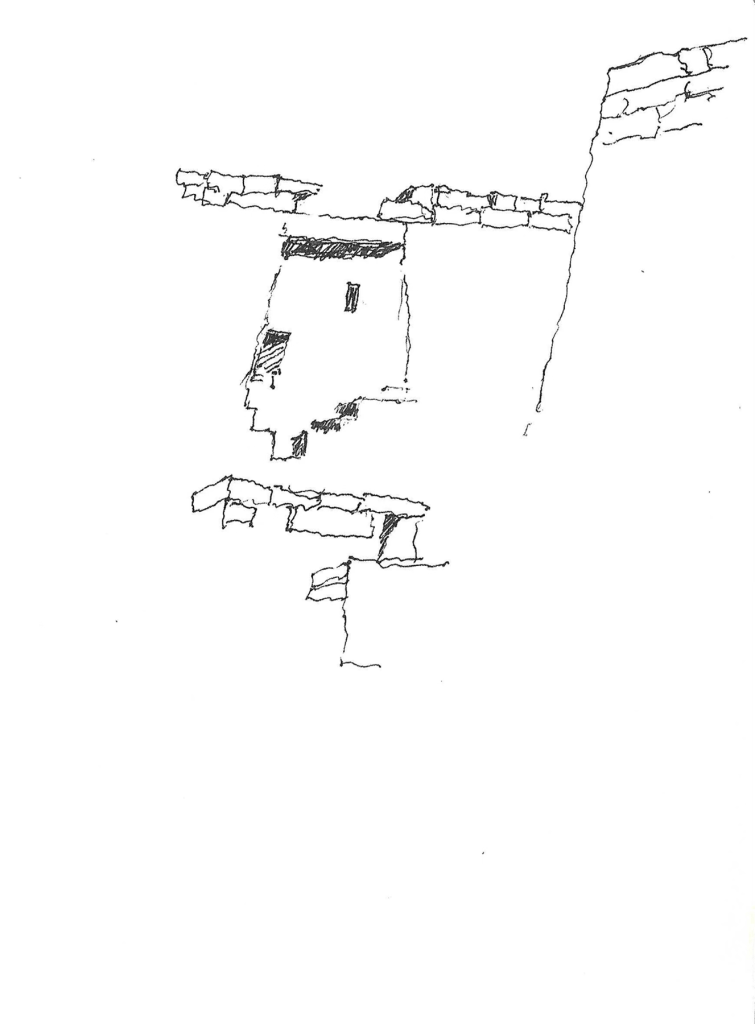

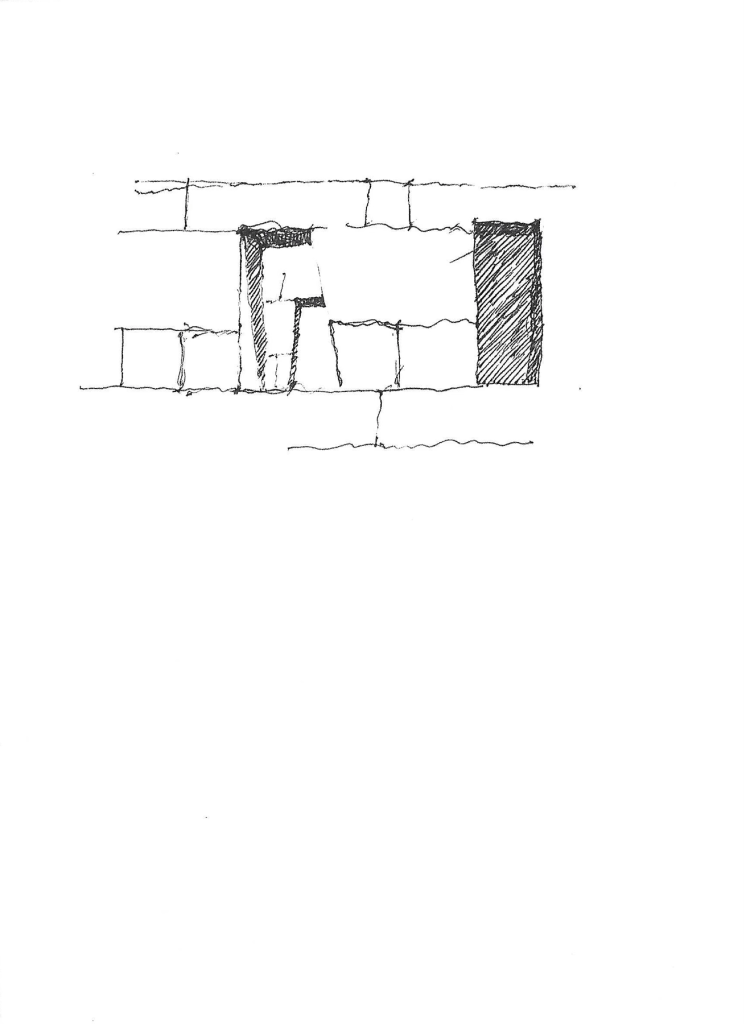

“Two Windows and a Niche”

30 October 2025

Pen & Ink on Paper

8 1/2” x 6”

“Two Niches”

30 October 2025

Pen & Ink on Paper

8 1/2” x 6”

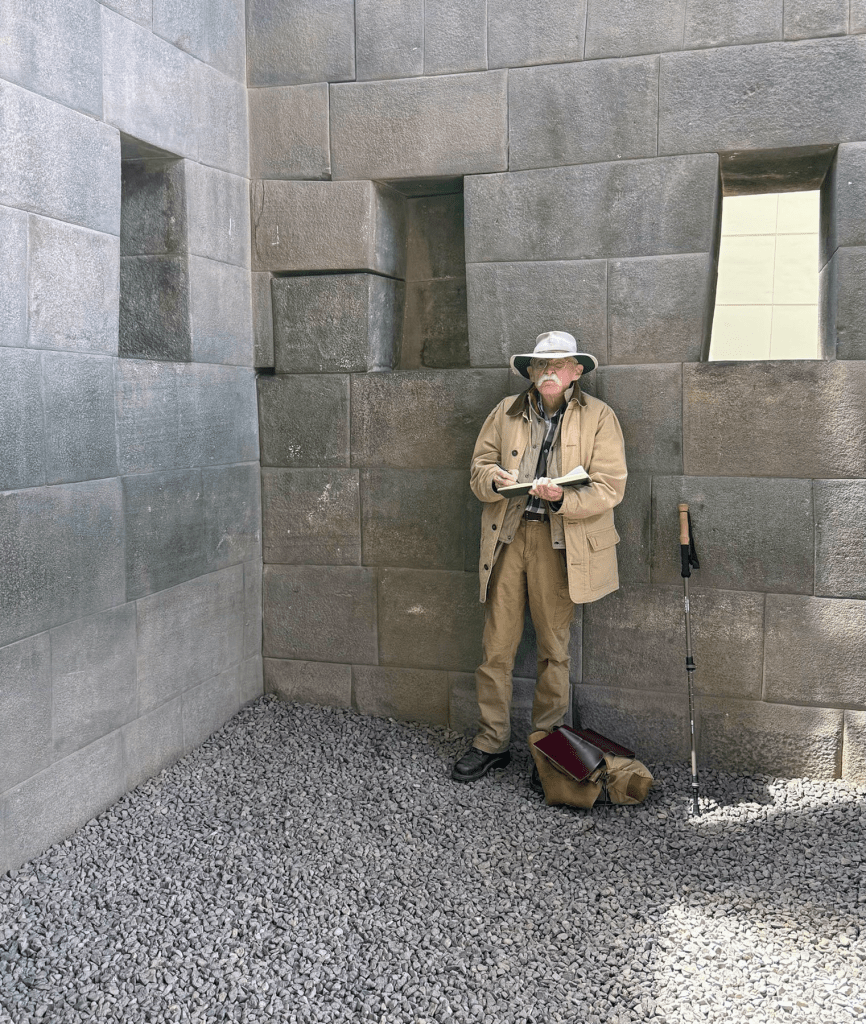

“The Artist Drawing at the original Qorikancha site in Cusco”

30 October 2025

Digital Photograph

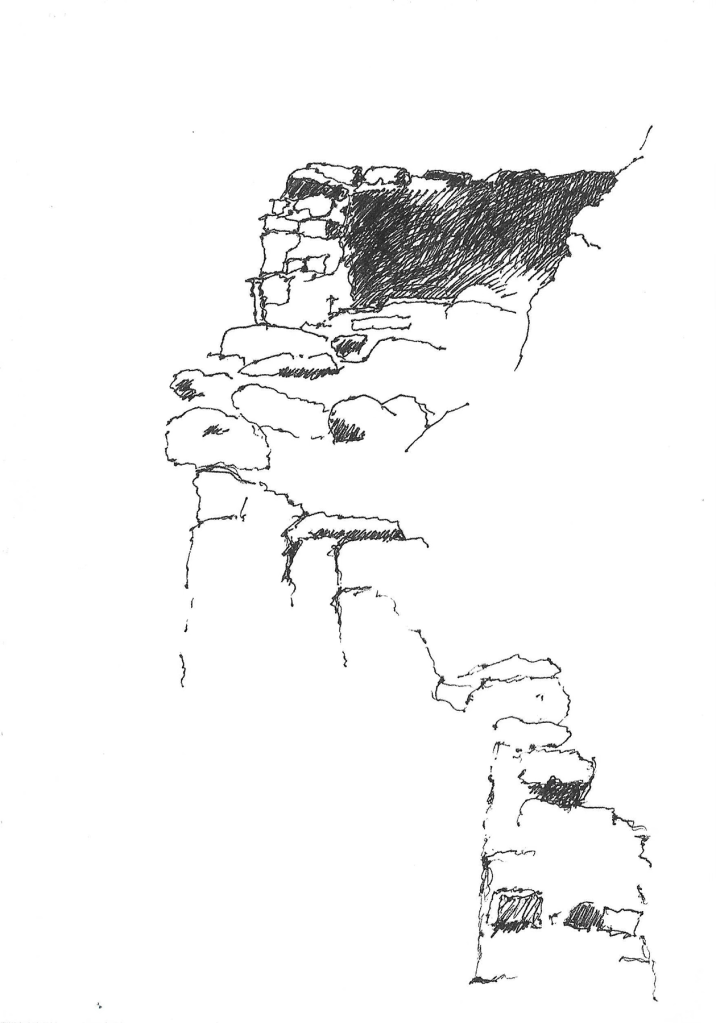

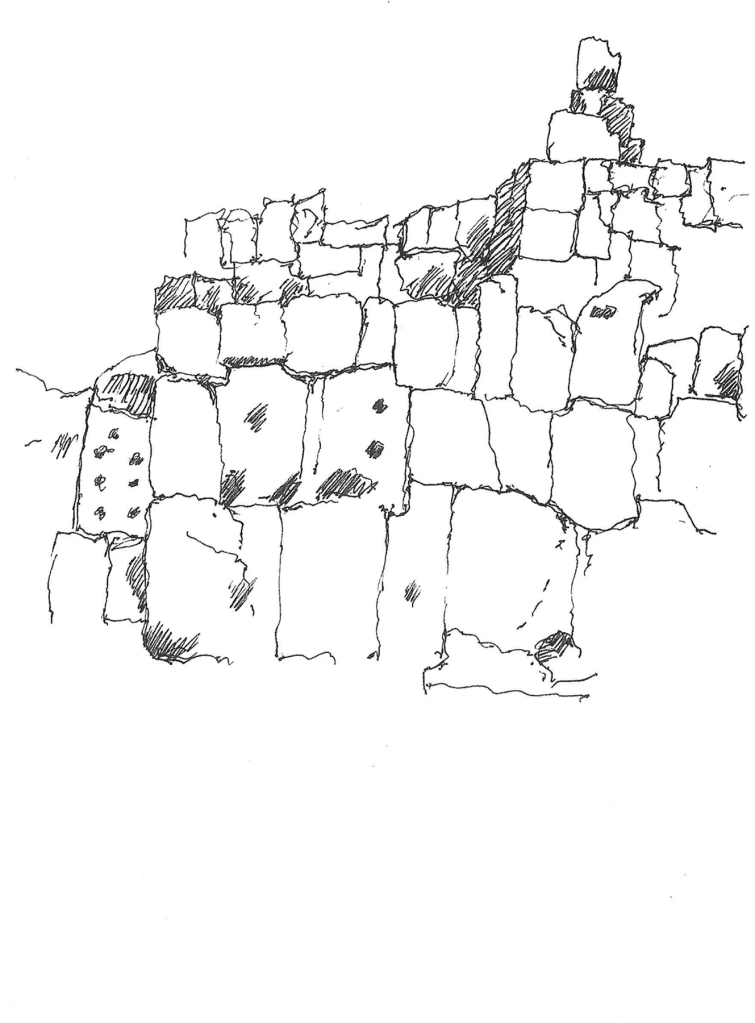

“The Giants of the Inca Wall at

Sacsayhuaman outside of Cusco”

1 November 2025

Pen & Ink on Paper

8 1/2” x 6”

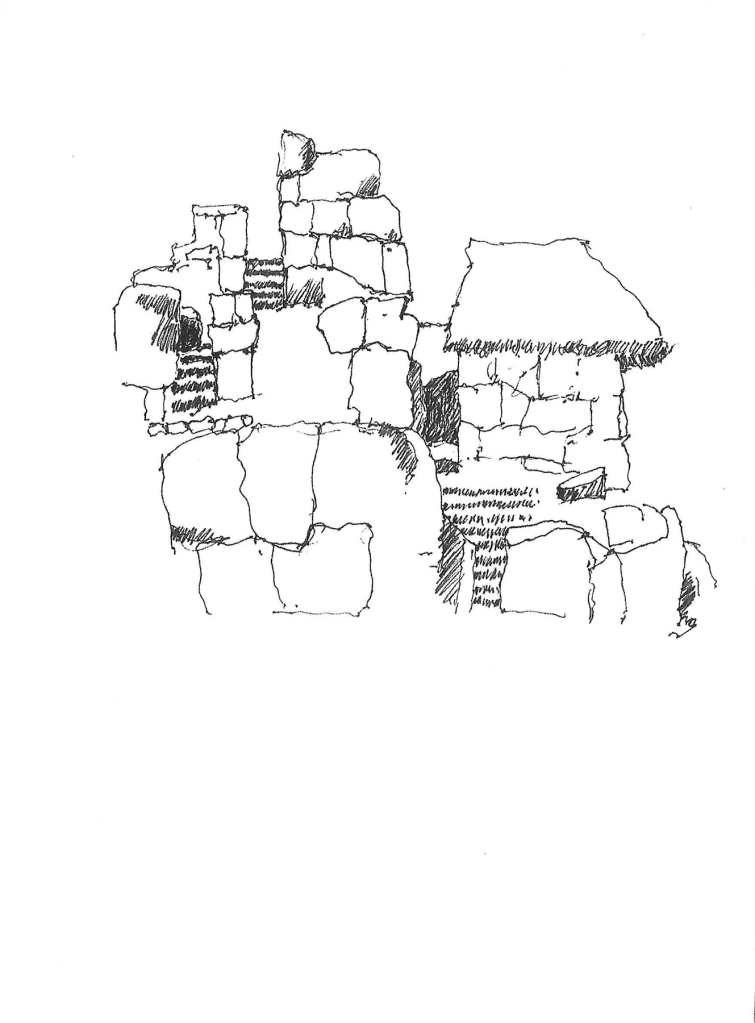

“The Third Grain Storage Shed at

Sacsayhuaman outside of Cusco”

1 November 2025

Pen & Ink on Paper

8 1/2” x 6”

Finally, with special thanks, particularly to Tom Lundberg and Kristen Thurber for their sensitive documentary photographs during this whole expedition, and to Wilson Jaimes for his understanding, strength and assistance in walking me back down from the very high path near the Inca Bridge.

1 Bingham, Hiram; Lost City of the Incas; Weidenfeld & Nicolson Publishers; London; 1952 & 2003; p. 197.

2 Bingham, Hiram; Lost City of the Incas; Weidenfeld & Nicolson Publishers; London; 1952 & 2003; pp. 184-185.

3 Bingham, Hiram; Lost City of the Incas; Weidenfeld & Nicolson Publishers; London; 1952 & 2003; pp. 184-185.

4 Adams, Mark; Turn Right at Machu Picchu: Rediscovering the Lost City One Step at a Time; Dutton, Random House; New York, New York; 2011; p. 183.

5 Adams, Mark; Turn Right at Machu Picchu: Rediscovering the Lost City One Step at a Time; Dutton, Random House; New York, New York; 2011; p. 4.

6 Neruda, Pablo; Thomas Q. Morin, translation; The Heights of Machu Picchu; Copper Canyon Press; Port Townsend, Washington; 2015; Section VI, pp. 17 & 19.